Continuity and aperiodicity

There are $2^{\Bbb Q} = \Bbb R$ continuous functions from $\Bbb Q \to \Bbb Q$ (1)

This theorem has been established and may be found in texts on real analysis, and one proof will suffice here.

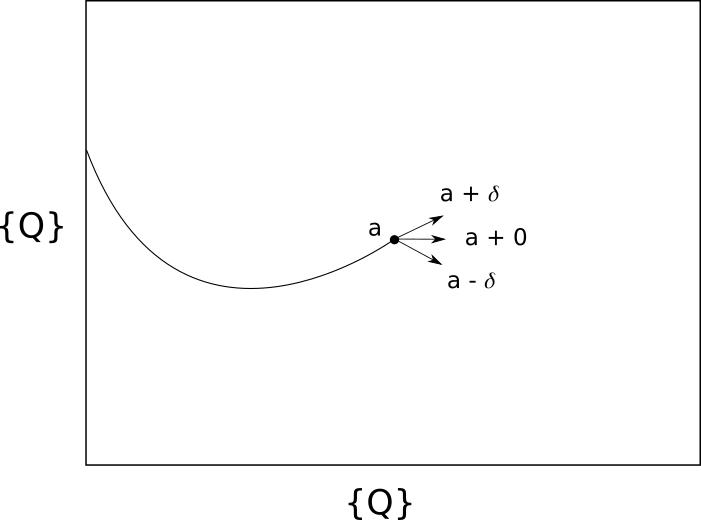

First we define a ‘unique’ function to define a single trajectory in finite dimension $D$. In other words, there is a one-to-one and onto mapping of a function to a trajectory. The coordinates for this trajectory are defined by members of the set of rational numbers $\Bbb Q$ for any continuous function. Now note that at any one point along a continuous trajectory, the next point is one of three options: it is slightly larger, slightly smaller, or the same. Graphically in two dimensions:

and precisely, $f$ may increase by $\delta$, decrease by $\delta$, or stay the same. Here $\delta$ is defined as

\[\lvert x_1 - x_2 \rvert < \epsilon \implies \lvert f(x_1) - f(x_2) \rvert < \delta\]for any arbitrarily small value $\epsilon$. Note that this is identical to the standard definition for continuity, which is $\lvert f(x_1) - f(x_2) \rvert < \epsilon$ for any $\epsilon > 0$ implies that there exists some $\delta$ such that $\lvert x_1 - x_2 \rvert < \delta$, but with $\epsilon$ and $\delta$ reversed.

Thus for $\Bbb Q$ there are three options, meaning that the set of continuous functions is equivalent to the set of all sets of $\Bbb Q$ into ${0, 1, 2}$

\[\{f\} \sim 3^{\Bbb Q} \sim \Bbb R\]or the set of all continuous functions defined on $\Bbb Q$ is equivalent to the set of real numbers.

There are $2^{\Bbb R}$ discontinuous functions from $\Bbb Q \to \Bbb Q$ (2)

Discontinuous trajectories in $Q$ may do more than increase or decrease by $\delta$ or else stay the same: the next point may be any element of $\Bbb Q$. The size of the set of all discontinuous functions is therefore the size of the set of all subsets of continuous functions. As we have established that the set of all continuous functions from $\Bbb Q \to \Bbb Q$ is equivalent to $\Bbb R$,

\[{2^{\Bbb Q}}^{\Bbb Q} = 2^{\Bbb R} = \Bbb R ^{\Bbb R}\]Another, perhaps more direct, proof of this statement is found here.

Discontinuous maps cannot be defined on the rationals (3)

Functions are simply subsets of the Cartesian product of one set into another, meaning that a function mapping $\Bbb Q \to \Bbb Q $ is a subset of

\[\Bbb Q^{\Bbb Q} = 2^{\Bbb Q}\]Thus there can be at most $\Bbb R$ functions mapping $\Bbb Q \to \Bbb Q$, but we have already seen that the size of the set of discontinuous functions is $2^{\Bbb R}$. This means that discontinuous functions cannot be defined on the set of rational numbers $Q$ for any finite dimension $D$.

Aperiodic maps are discontinuous (4)

Sensitivity to inital values can be defined such that an arbitrarily small difference $\varepsilon$ bewteen $x_0$ and $x_1$ leads to a difference $\Delta$ where

\[\exists n : \;\Delta = \lvert f^n(x_0) - f^n(x_1) \rvert\]such that $\Delta$ is not arbitrarily small. Sensitivity to initial values implies aperiodicity in bounded trajectories, as first recognized by Lorenz. Therefore aperiodic maps are necessarily sensitive to initial values.

Function $f$ is defined to be a continuous function from $\Bbb R^3 \to \Bbb R^3$ such that future values do not match previous ones. An example of $f$ could be an ordinary differential equation system for the Lorenz attractor. Now define a function $g$ that is equivalent to the composition of function $f \circ f \circ f …$. We can call $g$ the map of $f$, in that it yields the final position of an initial value $x_0$ in $\Bbb R$ after $n$ compositions. One $f$ yields one $g$ after an infinite number of compositions

\[f \circ f \circ f \circ f...\]$g$ is necessarily sensitive to initial values, due to the definition of $f$.

Corollary: $g$ for an arbitrary aperiodic map is discontinuous

Proof: Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $g$ is continuous. By definition, for all points $x_a, x_b$ and for any finite $\epsilon > 0$, there exists a $\delta > 0$ such that

\[\lvert g(x_a) - g(x_b) \rvert < \epsilon \\ \mathtt{whenever} \; \lvert x_a - x_b \rvert < \delta\]But if this was true of $g(x_a)$ and $g(x_b)$ for all $g$ then $\lvert g(x_a) - g(x_b) \rvert < \epsilon \; \forall \epsilon$ given a finite $\delta$ such that $\lvert x_a - x_b \rvert < \delta$. But then if $x_a - x_b < \delta$ then $g(x_a)$ would stay arbitrarily close to $g(x_b)$ and $g(x)$ would not be sensitive to arbitrarily small changes in initial points $x_a, x_b…$. This is a contradiction by the definition of $g$ above, and therefore $g(x)$ is discontinuous. $\square$

Finally, note that we can define the map of an aperiodic, bounded function $f$ based on $g$ for an infinite number of compositions $f$. Taking $g$ as our aperiodic map, the result is that aperiodic, bounded phase space maps are discontinuous.

Aperiodic, bounded maps cannot be defined on $\Bbb Q$ (5)

This results from (3) and (4).

And now we conclude the (informal but hopefully accurate) theorem-proof portion of this page.

How a composition of continuous functions can be discontinuous

Given a continuous function, say $f(x) = x^2$, the composition of this function with itself is

\[f \circ f =f(f(x)) = (x^2)^2 = x^4\]and $x^4$ is also continuous. Indeed any finite number of compositions of $f$ will be continuous. But consider that there are an infinite number of compositions required for a map of an ordinary differential equation system over any finite length of time. This means that no finite number of compositions of $f$, or an ability to show that this composition is continuous can convince us that $g$ is continuous.

For a discontinous functions, an infinitely small change in the input does not correspond to an infinitely small change in the output but rather a certain finite amount. For our composition map $g$, this finite change in the output is the result of multiplication of infinitely small changes in outputs of $f$ (as $f$ is continuous) by an infinite number (of compositions). This is reminiscent of integral calculus, where the multiplication of an infinite number of infinitely small quantities yields a finite positive output.

This is conceptually the mirror image of the idea that nonlinear ordinary differential equations can lead to evaluation to infinity in a finite amount of time. An example of this is for the differential equation

\[f(x) = 1 + x^2 \\ x_0 = 0\]then

\[dx/dt = 1 + x^2 \\ \frac{dx}{1+x^2} = dt\]and integrating for time,

\[\int \frac{dx}{1+x^2} = \int dt \\ tan^{-1}(x) = t + C \\\]For the definition of $g$ as the composition of $f$ at finite time $t$, $g(t) = tan^{-1}(x) + C$ meaning that $g$ reaches $\pm \infty$ when $t \ge \pi/2$. Note that $f(x_0) = 1$, meaning that an infinite value has been reached in finite time for compositions of this $f$.

Smale’s horseshoe map

Stephen Smale introduced the horseshoe map to describe a common aperiodic attractor topology. This model maps a square into itself such that the surface is stretched, folded and then re-stretched over and over like a baker’s dough. The horseshoe map is everywhere discontinuous as points arbitrarily close together to start are separated (the surface is stretched at each iteration and there are infinite iterations) such that there is a distance greater than some $e > 0$ between them. The process of folding prevents divergence to infinity.

As an aside, it is also interesting to note that stretching and folding is the most efficient way to mix physical substances that have internal cohesion. For example, take two substances that are malleable solids. Being solids, they have internal cohesion strong enough to prevent mixing due to gravity if someone puts the solids in the same container. This self-attraction makes it difficult to mix the solids by jostling or otherwise adding energy to the container. Rather, iteratively stretching out each solid (maintaining some internal attraction while increasing surface area) and then folding them together uses less energy (cohesive forces do not need to be overcome).