Puzzles

Connect Four winner decider

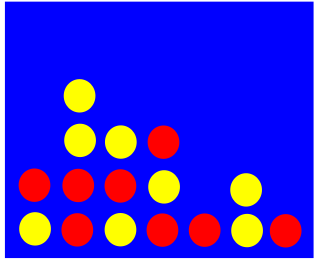

Let’s take a series of moves and determine a winner for the classic turn-based game Connect Four. This was one of my favorite games growing up! It is played by dropping colored disks into a vertical 7 x 6 board such that each disk played rests on the disks (or base) below. The winner is the first player to connect four disks of their color in a vertical, horizontal, or diagonal row.

For the list of moves, a series of moves by each player may be represented by a list of strings as follows:

moves_list = ["F_Yellow", "A_Red", "D_Yellow", "D_Red", ... ]

Here each player is denoted by the color of their piece, and each move is denoted by the letter ‘A’ or ‘D’ etc. of the row that they put their piece into.

To determine the winner of any given move list, the strategy is simple: add each move to a matrix representing the game board, and check whether any four pieces are connected at each turn. To start with, define a function that takes in the move list and returns the winner if there is one and write a docstring that tells us what the funciton will do:

def connect_four_winner(moves_list):

'''A function that takes a list of connect four moves (each

move in the format of X_color where X is the row of piece addition

and color is the color of the piece moved) and returns the winning

color, or 'Draw' if there is no winner.

'''

The next step is to initialize a board by using a matrix. The game board is 7 slots wide by 6 slots high, but it turns out that using a bigger board makes finding connected pieces more simple to program. Here is a 10 x 9 slot list of lists representing a board. The reason behind making the board larger will become clear in a moment.

# initialize the board

board = [[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0]]

Now let’s add each move to the board, one by one. Abitrarily classifying 'Red' as player 1 and 'Yellow' as player 2, each move in the list of moves is positioned by determining who moved.

for move in moves_list:

if move[2:] == 'Red':

piece = 1

else:

piece = 2

To determine where each player’s piece lands, the letter corresponding to the row played is counted and the piece is added to the first open slot (open slots are denoted '0') in that row. Our board is upside down, being filled top to bottom! This does not matter for determining the winner, however. The code above is omitted using '...' for clarity.

for move in moves_list:

...

for i, letter in enumerate('ABCDEFG'):

if move[0] == letter:

for k in range(6):

if board[k][i] == 0:

board[k][i] = piece

break

Note that pieces are added to the 7x6 slots in the lower left hand corner of the entire 10x9 board. Now it is clear why this is: after adding each piece to the board as above, it is easy to check if there are four slots of a color occupied in a row, column, or diagonal by iterating accross every position of the 7x6 board as a starting point. 10x9 comes from adding 3 to both width and height of the board, such that there are not index errors as one traverses each position of the real board. The slots outside the real board remain empty ('0'), and so do not influence whether or not a player wins.

for move in moves_list:

...

...

for i in range(6):

for j in range(7):

# check for a horizontal four

count = 0

for k in range(4):

if board[i][j+k] == piece: count += 1

else: break

if count == 4:

return 'Red' if piece == 1 else 'Yellow'

# check for a vertical four

count = 0

for n in range(4):

if board[i+n][j] == piece: count += 1

else: break

if count == 4:

return'Red' if piece == 1 else 'Yellow'

# check for diagonal four right

count = 0

for r in range(4):

if board[i+r][j+r] == piece: count += 1

else: break

if count == 4:

return 'Red' if piece == 1 else 'Yellow'

# check for diagonal four left

count = 0

for s in range(4):

if board[i-s+3][j+s] == piece: count += 1

else: break

if count == 4:

return 'Red' if piece == 1 else 'Yellow'

return 'Draw'

The trickiest part here is finding backwards diagonals, ie pieces arranged in a \ pattern. If we start at [0,0], an index error will be thrown because there is no -1 index in this list of lists! Instead, we offset the starting horizontal value by 3 such that all 4 slots tested are within the matrix size. Looking at a physical board should make it clear why this is a valid way to test for diagonals, even if not all pieces of the ‘real’ board are being tested. If there is no winner after all moves are made, 'Draw' is returned.

for move in moves_list:

...

...

...

# check for diagonal four left

count = 0

for s in range(4):

if board[i-s+3][j+s] == piece: count += 1

else: break

if count == 4:

return 'Red' if piece == 1 else 'Yellow'

return 'Draw'

Let’s test it out! The following move list results in a win by Red

moves_list = [

"F_Yellow", "G_Red", "D_Yellow", "C_Red", "A_Yellow", "A_Red", "E_Yellow", "D_Red", "D_Yellow", "F_Red",

"B_Yellow", "E_Red", "C_Yellow", "D_Red", "F_Yellow", "D_Red", "D_Yellow", "F_Red", "G_Yellow", "C_Red",

"F_Yellow", "E_Red"]

and if we print the board after adding each piece as a matrix by inserting the following into the moves loop:

import pprint

pprint.pprint (board)

we see that the final board indeed has a diagonal four for red, in fact it has two!

[[2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 2, 1, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

The full code is available here

Sudoku solver

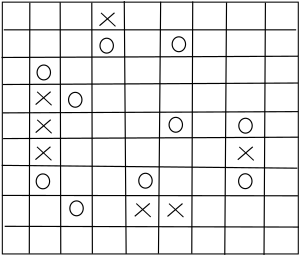

Let’s write a program to solve a sudoku puzzle! Sudoku puzzles involve placing numbers 1-9 in squares on a 9x9 grid with some numbers filled in (above) such that every row or column contains one of each digit, and every smaller 3x3 square in bold also contains only one digit (ie no two 9s or two 1s).

There are a number of advanced strategies that once can use for this puzzle, but if time is not a limiting factor then we can use a very simple method to solve any given puzzle. The method is guess and check: for each empty grid space, let’s add a number between 1 and 9 and see if the puzzle is OK. If so, we continue on to the next grid but if not we simply increment the number tried (if 1 did not work, we try 2 etc.). If none of the numbers work, we go backwards and increment the number in the previous grid, and if none of those work we go backwards until a number does work. This method is often called backtracking, and there are a number of useful animations online for observing how this works.

The reason this algorithm works is because it potentially tries every combination of digits in the empty boxes, so if there is a possible solution then the solution will eventually be found! The program we will write here usually runs in a matter of tens to hundreds of milliseconds on challenging puzzles, but can take up to half a minute or more on extremely difficult ones. The sample problem here is challenging, and takes approximately a second to solve.

Let’s represent the Sudoku board as a matrix, which we can specify as a list of lists (1-dimensional arrays, to be precise) without having to resort to a library like numpy to make fancy two-dimensional arrays. Here is the representation of the puzzle above:

puzzle = [

[0, 0, 4, 0, 0, 1, 7, 0, 0],

[0, 8, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[2, 0, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 5, 0, 3, 0, 7, 8],

[0, 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 0],

[9, 6, 0, 1, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 9],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 6, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 7, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0]]

Now is the time to define a function, remembering a doc string that specifies valid inputs and expected outputs:

def solve(puzzle):

'''A function that takes a list of lists denoting sudoku

puzzle clues and places to guess (0s) and returns the completed

puzzle as a list of lists. Expects a solveable puzzle, and will

return only solution if multiple exist.

'''

It is helpful to know which positions on the puzzle we need to try numbers, and which positions are given. With a nested loop, we can make a list named ls of all coordinates of positions of to-be-found values as follows:

# make list of all positions to be determined

ls = []

for x in range(9):

for y in range(9):

if puzzle[x][y] == 0:

ls.append([x,y])

# call backtracking function (below)

return backtrack(puzzle, ls)

Now let’s apply the backtracking algorithm to the puzzle, but only on the positions of values to be found, by indexing over the list ls. One can define another function within the first to do so, which is not absolutely necessary but provides clarity.

def backtrack(puzzle, ls):

'''Solves the sudoku puzzle by iterating through the

positions in ls and entering possible values into

the puzzle array. Backtracking occurs when no entry

is possible for a given space.

'''

i = 0

while i in range(len(ls)):

a, b = ls[i]

so now (a, b) is set to the coordinates of the first unknown space. This is a good time to initialize a variable count to be 0, which will change to 1 if a digit cannot be inserted at the unknown space. If there are no legal moves in the first unknown space, the puzzle is not solveable! The count becomes important in subsequent spaces, and signals the need to backtrack: if no digit can be insterted at a space, then count stays 0 and we will add a clause to initiate backtracking if that is the case. Let’s also initiate the variable c, which will store the next number to be tested as follows:

count = 0

if puzzle[a][b] == 0:

c = 0

else:

c = puzzle[a][b]

c += 1

Now come the tests: first the row (which is equal to puzzle[a]), then the column (ls2), and finally the 3x3 box (ls3) are tested to see if c is different than every element of these three lists.

while c < 10:

if c not in puzzle[a]:

ls2 = []

for q in range(9):

ls2.append(puzzle[q][b])

if c not in ls2:

ls3 = []

x, y = a // 3, b // 3

for k in range(3*x, 3*x+3):

for l in range(3*y, 3*y+3):

ls3.append(puzzle[k][l])

if c not in ls3:

If c is a unique element, it is a possible move! If so, we add it to the puzzle by assigment, increment our variable ‘count’, and increment the index of the list of coordinates to be solved (i) and break out of the while loop. If any of these tests fail, c cannot be a valid move for the position ls[i], so we increment c and continue the loop to test the next larger digit.

puzzle[a][b] = c

count += 1

i += 1

break

else: c += 1

else: c += 1

else: c += 1

If no digit 1-9 is a legal move at the given position the ‘count’ variable stays 0 and we use this to test whether a backtrack needs to be made. If so, we return the current position to 0 and decrement the index of the list of coordinates to be solved (i). If all elements of this list have been iterated, we must have filled in a number at all positions so we can return the solved puzzle. Finally we call the intertior function backtrack() in the exterior function solve() with the arguments of the puzzle and the list of places to fill in.

if count == 0:

puzzle[a][b] = 0

i -= 1

return puzzle

Markdown is not good a tracking spaces between code entries, so make sure to line up each if/else and loop The full sudoku solver code is available here.

Now let’s test the solver! Pretty printing (each element of a list is given its own line) is helpful here to make the matrix readable, so let’s add the input and pprint it).

# example of an input

puzzle = [

[0, 0, 4, 0, 0, 1, 7, 0, 0],

[0, 8, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[2, 0, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 5, 0, 3, 0, 7, 8],

[0, 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 0],

[9, 6, 0, 1, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 9],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 6, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 7, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0]]

# example function call

import pprint

pprint.pprint (solve(puzzle))

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[[5, 9, 4, 8, 3, 1, 7, 2, 6],

[7, 8, 3, 4, 2, 6, 9, 1, 5],

[2, 1, 6, 9, 7, 5, 8, 3, 4],

[1, 4, 2, 5, 9, 3, 6, 7, 8],

[8, 3, 5, 2, 6, 7, 4, 9, 1],

[9, 6, 7, 1, 8, 4, 3, 5, 2],

[3, 7, 8, 6, 5, 2, 1, 4, 9],

[4, 2, 9, 3, 1, 8, 5, 6, 7],

[6, 5, 1, 7, 4, 9, 2, 8, 3]]

[Finished in 0.9s]

The output looks good! No 0s remaining and no obvious errors in digit placement. Running this program on pypy for speed, the time is down to 183 ms.

(base) bbadger@bbadger:~/Desktop$ time pypy sudoku_solver.py

... (matrix shown here) ...

real 0m0.183s

user 0m0.144s

sys 0m0.021s

Battleship placement validator

Say you are playing battleship the old fashioned way: with paper and a drawn 10x10 grid. You mark the positions of your ships with ‘1’s, but after doing so wonder if you made a mistake. Is your battleship field valid according to the rules that ships may be touching each other, and ships comprise of one carrier size 4 square, two battleships size 3, three destroyers size 2, and four subs of size 1?

We can represent the battleship grid with a list of lists corresponding to a matrix:

field = [[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

How do we go about determining if this is a valid field? A simple test that comes to mind is to count the number of positions and determine if this number exceeds or falls short of what it should be (20), which can be accomplished by nesting two loops and incrementing a counter for each position with a ship (denoted 1).

# preliminary check for the correct number of spaces

count = 0

for lst in field:

for element in lst:

if element == 1:

count += 1

if count != 20:

return False

But for all the combinations of placements where there are the correct number of positions marked, how do we tell which ones are valid and which are not?

Suppose there was only one ship, a carrier. Then the problem is easier, and it is a simple task to see if the field is valid: simply loop over each element of the field (left to right and top to bottom is the order for two nested loops) and for the first 1, see if there are three other 1s to the right or below. The trailing 1s will not be above or behind because then we would not be observing the first 1! If there are indeed three 1s behind or below the first but no more 1s anywhere else, we have a valid board and vice versa.

With two ships this becomes more difficult. To which ship does the first 1 belong to? If we ignore this question and assume that the 1 belongs to one particular type of ship, we may mistakenly classify an invalid board as valid (or the opposite) because ships can be touching. But it is impossible to know which 1 belongs to which ship, so how do we proceed?

Making the problem smaller certainly helped, and this is a sign that recursion is the way forward with this problem. Using recursion, we can start with a grid with many 1s and eliminate them as we guess which pieces belong to which ship. We work around the problem of not knowing which ship is associated with each 1 by simply trying every option possible, and if any are valid then we have a valid board setup!

Let’s define a function and attach a docstring. A list of ships will be useful, so we define a list ships using the ship size as the names for each ship. As we will be checking each position to determine if it is a part of the ship, it is helpful to add 0s along the right and lower borders of our matrix such that we avoid index errors while checking all 1s. Here we include a layer of 0s along the upper and left borders of the matrix for visual clarity. Our preliminary check for the correct number of ship spots is added here too.

def validate_battlefield(field):

'''A function that takes a 10x10 list of lists corresponding to a

battleship board as an argument and returns True if the field is

a legal arrangement of ships or False if not. Ships are standard

(1 carrier size 4, 2 battleships size 3, 3 destroyers size 2, 4 subs

size 1) and ships may be touching each other. Only the location of

hits are known, not the identity of each hit.

'''

ships = [4, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1]

import pprint

# make a wrapper for the field for ease of iteration

for i in field:

i.insert(0, 0)

i.append(0)

field.insert(0, [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

field.append([0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

# preliminary check for the correct number of spaces

count = 0

for lst in field:

for element in lst:

if element == 1:

count += 1

if count != 20:

return False

# call a validate function on the prepared field

return validate(field, ships)

Now comes the recursion. To avoid re-wrapping the field with 0s and re-checking to see if the correct number of spots are filled, we can define another function in this larger one and simply call this one. The strategy will be iterate along the original field until we see a 1, and then test if it can be the largest ship in the vertical direction. If so, we remove all 1s corresponding to this ship on the field, remove the largest ship from the list ships, and copy the ships list (to avoid errors during recursion).

We then test whether this copied list is valid by calling the validate function on this list with the copied ships ships2, which causes the function validate to be called over and over until either the list ships has been exhausted, or until there are no other options for piece placement. If the former is true, the board is valid and the function returns True, otherwise False is returned up the stack.

When False reaches the first if validate() statement, it causes the program to skip to else, where we add back the ship we earlier erased from the board. Otherwise many invalid boards will be classified as valid! The horizontal direction must also be considered at each stage, so the code above is repeated but for check along each list. At the end, a last check for any remaining ships is made, and this function is called inside validate_battlefield().

def validate(field, ships):

'''Assesses the validity of a given field (field), with a

list of ships that are yet to be accounted for (ships). The

method is to remove ships, largest to smallest, using recursion.

Returns a boolean corresponding to the possibility of the field

being legal or not.

'''

for i in range(12):

for j in range(12):

if field[i][j] == 1:

k = 0

while field[i+k][j] == 1:

k += 1

if k == ships[0]:

del ships[0]

for m in range(k):

field[i+m][j] = 0

if len(ships) == 0:

y = 1

return True

ships2 = ships[:]

if validate(field, ships2):

return True

else:

for x in range(k):

field[i+x][j] = 1

ships = [k] + ships

w = 0

while field[i][j+w] == 1:

w += 1

if w == ships[0]:

del ships[0]

for n in range(w):

field[i][j+n] = 0

if len(ships)==0:

y = 1

return True

ships3 = ships[:]

if validate(field, ships3):

return True

else:

for n in range(w):

field[i][j+n] = 1

ships = [w] + ships

if len(ships)==0:

return True

else:

return False

Let’s test this out! With the battlefield shown above, we get

# example function call

print (validate_battlefield(field))

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

True

[Finished in 0.0s]

Manually trying to put ships in place should convince you that the field is indeed valid!