Nonlinear tranformations as routes between dimensions

Here ‘nonlinear transformations’ is taken to mean the set of all equations that are nonlinear (ie any non limited to unary exponents) or piecewise linear.

Transformations from finite to infinite size

In set-theoretic geometry, there are as many points in a line of finite length than there are in the entire real number line, which is of infinite length. This means that there can be some function $f$ that maps each point of a finite line segment to each point on the number line, or in other words that there is some function $f$ that maps a finite length onto an infinite one bijectively.

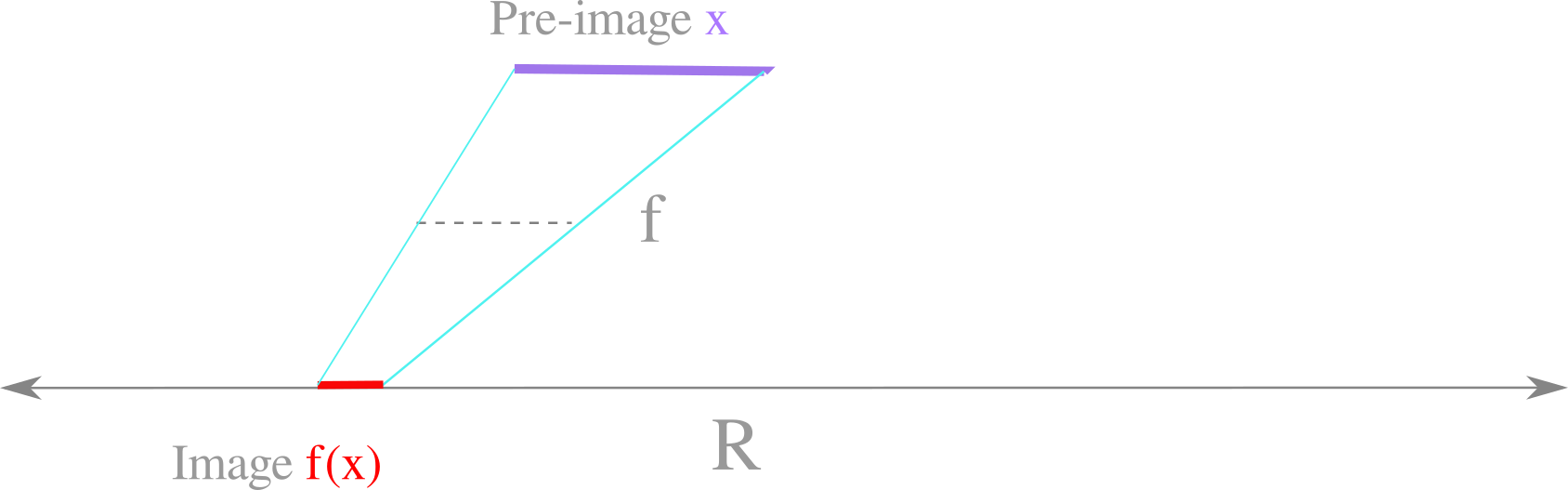

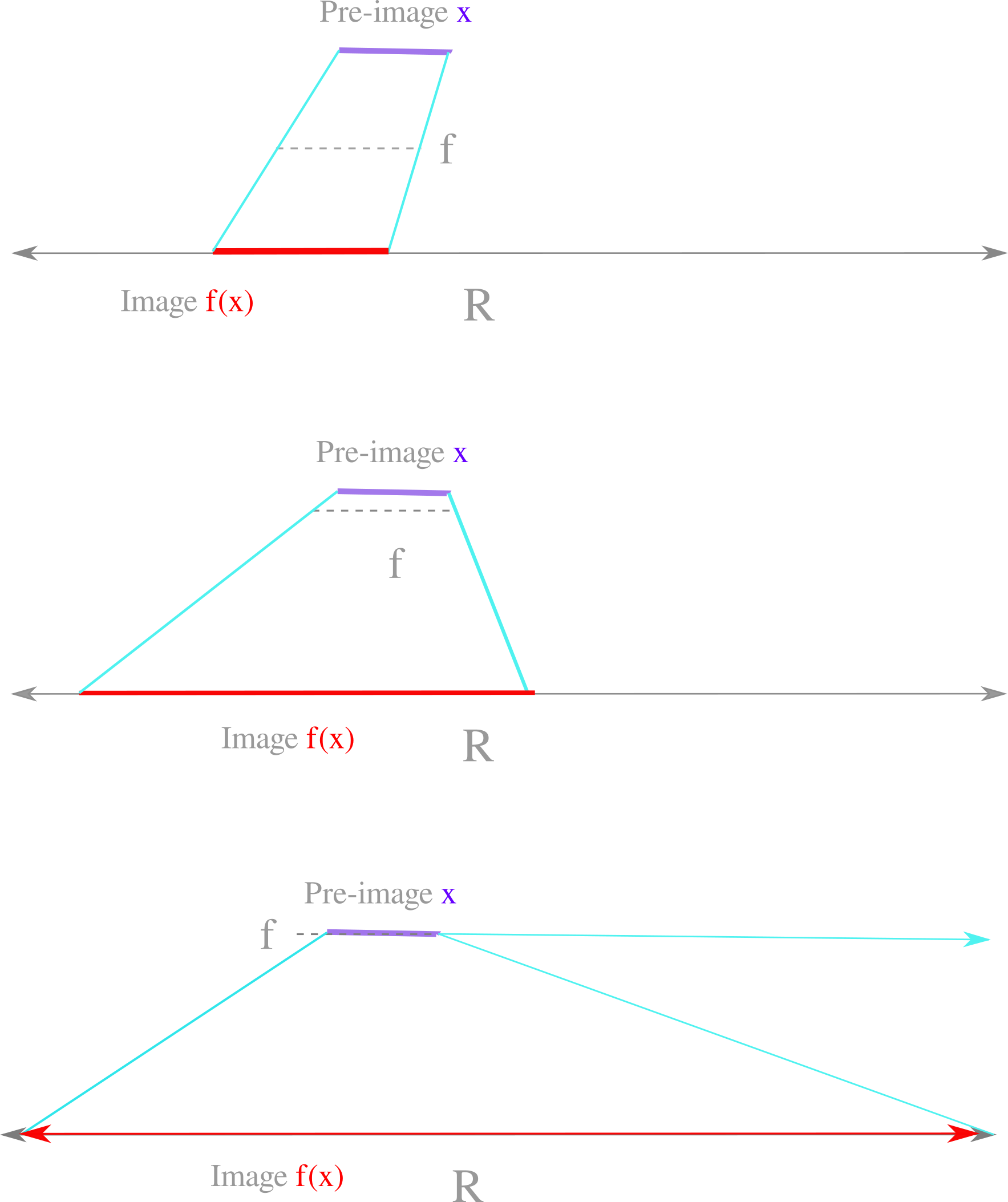

Therefore an object in one dimension of finite length may be mapped to the entire real line with the right transformation. Which transformations can accomplish this? Transformations may be defined as lines or curves or points that map the finite line segment (specifically an open subset of $\Bbb R$, for example the points of $x \in (0, 1)$ into the real line $\Bbb R$ as follows:

Only a curve (or line segments arranged to approximate a curve if corners are ignored) can map the segment to the entire real line.

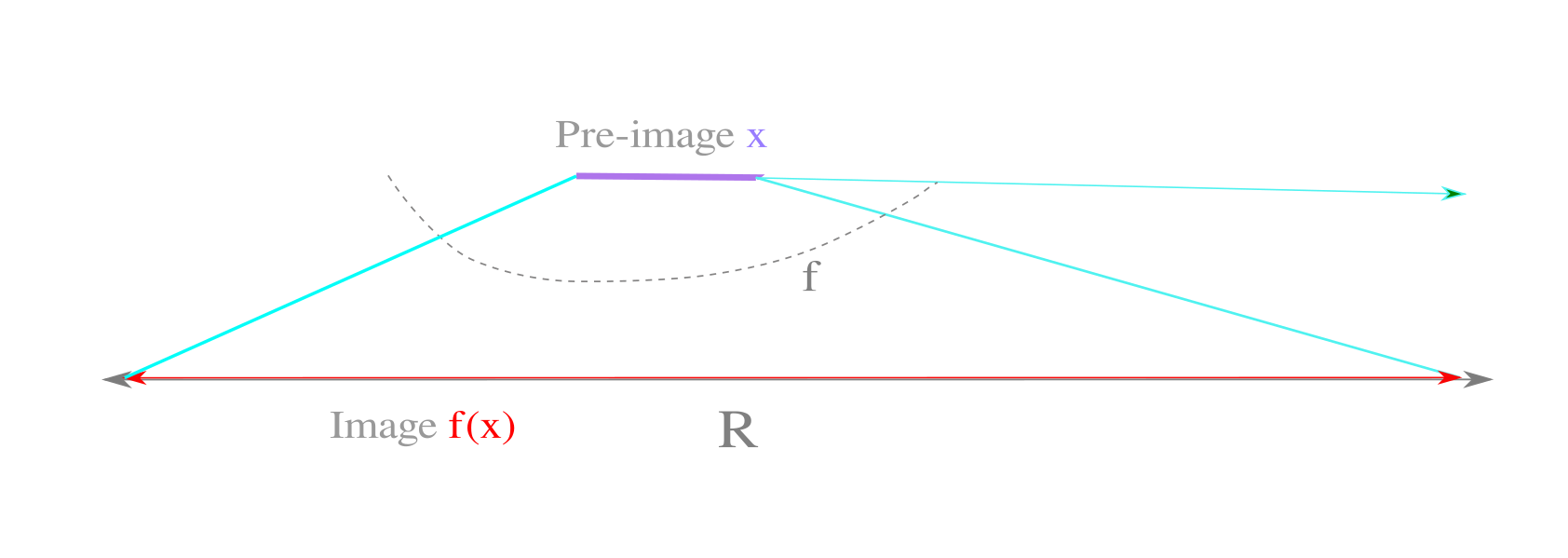

This can be seen most clearly by observing what happens when the starting line approaches a linear map, ie a line. More and more of the reals may be mapped but the distance is always finite until the mapping (the transforation) is on top of the line segment (the pre-image).

When the transformation lies on top of the pre-image, it may accurately be said that the transformation is the pre-image. But this transformation is no longer a function at all, as it is a one-to-many transformation because any point on the pre-image line segment is in the same place as a point on the transformation, meaning that the image point may exist anywhere.

This is a graphical illustration of a function in which the input is the same as the function itself. If the Church-Turing thesis is accepted, these functions can be equivalently stated as Turing machines $T$ in which the program $a$ is the same as the input $i$. It is provable that such machines never halt: the predicate ‘does the turing machine $T$ with input $i$ and program $a$ where $i=a$ halt at value $x$ for some value $x$’, in symbols $\exists x T(a, a, x)$, is undecidable. If such a machine halted at any $x$, the predicate would be decidable but as it is not, a Turing machine with its program as the input never halts.

All this is to say that the transformation of a line on top of another line may map a segment to the entire real line but that this is no longer a function, nor is it computable. Therefore, only nonlinear functions are capable of mapping a finite segment onto the entire real line.

Increases in topological dimension require nonlinear transformations

Topological dimension and scaling (fractal) dimension are equivalent for the classical objects in which topological dimension is defined: a point is 0-dimensional, a line 1-dimensional, a plane surface two-dimensional etc. A mapping from one topological dimension to another that is larger requires a transformation to infinite size. A proof for this for the case of a 1-D line transformed into a 2-D plane is as follows: first suppose that a finite line could be arranged to cover a plane. As the line is of finite size, an increase in scale will eventually lead to gaps between portions of this line: if this were not the case,

As seen in the previous section, only nonlinear transformations map finite sizes to infinite. Therefore transformations from one topological dimension to a larger one must be nonlinear.

Curve dimension

Here dimension is not fractal or topological, but a definition based on the transformations that can result from a function. Take an arbitrary line existing on a plane. In some orientation, this line may be defined entirely on the basis of another line that exists alone, ie in one dimension.

Now note that this is not the case for an arbitrary curve on a plane: this curve by definition is not congruent to any of the lines mentioned above. The curve may be mapped to a line, but it is not equal in that it cannot be substituted for any line. Therefore a curve cannot be defined in one dimension, because otherwise it would be congruent with a line.

This idea extends to curved surfaces in three dimensions. Such surfaces are not entirely planar but exist in three dimensions, and therefore are not congruent with a topologically two-dimensional plane. This goes to suggest that curves of any kind exist between topological dimensions, which provides a clear reason why nonlinear transformations are capable of providing routes between topological or fractal dimensions.

Dimension-changing maps are uncomputable

Space-filling Hilbert or Peano curves require an infinite number of recursions. Infinitely recursive functions are undecidable, and therefore space-filling curves are undecidable.

Dimension-changing maps require an infinite number of recursions as well, and therefore dimension-changing maps are undecidable. For more on decidability, see here.

Why nonlinear transformations are not additive, from a set-theoretic perspective

Non-additivity is a defining feature of nonlinearity. But what does it mean that nonlinear transformations are not additive, which in symbols is

\[f(a+b) \neq f(a) + f(b)\]in the sense of how is this possible? This means that the transformation specified by $f$ must be different at different locations, such that the location $a+b$ is a different transformation than that which is found at $a$ or $b$ and that simply performing the transformation at $a$ then at $b$ is not sufficient to predict the transformation at $a+b$. In a sense, the transformations are unique for every element of the pre-image.

But this remains a somewhat counter-intuitive idea. We can define the set of all possible transformations for any given $f$ as $\mathscr S$. As all finite quantities can be added, elements $a$ and $b$ of $\mathscr S$ are not finite. An infinite set is equivalent to one of its proper subsets, meaning that inside elements $a$ and $b$ there are more of $a$ and $b$.

Now recall that most nonlinear transformations are aperiodic and that bounded, aperiodic maps form self-similar fractals. The observations that $a \in a$ (proper subset) gives a clear reason why such objects exist: each fractal image $i$ contains a smaller version of itself, meaning that $i \in i$ (proper subset, as the smaller version does not contain all points of the larger).

Here is another argument arriving at the same concusion: Sets cannot be partitioned arbitrarily. To see that this statement is true, consider what happens if we try to partition a set $A$ into partition sets $S_1, S_2, S_3 …$ where members are larger than the other members of the same partition. It is not clear which elements belong with which others, or even if an element belongs in its own set.

Somewhat surprisingly, the only way to partition a set is via an equivalence class: each element in a given partition $e_1 \in P$ must be somehow equivalent to each other element $e_2, e_3, … \in P$. For example, suppose that we want to partition the set of natural numbers $\Bbb N$ based on size: numbers larger than 5 in one partition, numbers smaller or equal to 5 in another. The equivalence of each partition is its relation to the number 5: either all larger or all smaller (or the same size). Imagine if partitioning did not necessarily involve equivalence. Then trying to partition a set into elements that are larger than each other would be possible, but it is unclear which elements belong in any given subset, or even if an element belongs in any subset, a contradiction.

Now consider a set $S$ where some elements are incomparable. There is no chance of partitioning $S$ because one cannot determine which elements of $S$ are greater or less than others, and thus we cannot be sure of which elements are equivalently larger or smaller (or equivalent in any way). If a set cannot be partitioned, then additivity cannot be valid from the definition given above. Therefore any set with incomparable elements is not additive.

Take collections of points transformed by a nonlinear function. Are such collections comparable to other collections? Comparability requires that for two elements $a, b$ either $a \geq b$ or $b \geq a$. Can we choose between statements if there exists an infinite number of elements $a$ in element $b$, while at the same time there are infinitely many $b$ in $a$? No, and therefore self-similar nonlinear maps contain collections of points that are incomparable by definition. As certain subsets are incomparable, the transformation itself is non-additive.

A concrete example of non-additivity

The underlying point here is that one arrives at problems when attempting to add infinite quantities, or in other words that infinite quantities are non-additive. As we saw earlier, nonlinear transformations have the capacity to map finite regions onto infinite, and indeed any fraction of the whole finite region may be mapped onto an infinite region. Because of the introduction of infinite quantities, nonlinear transformations are not additive.

To show how a infinite quantities lead to the inability of additivity, consider the following problem: a hybrid car (perhaps a prius) is driving along a road that is relatively flat. The car dislays the gas milage at each point along the trip, and we assume that this display is accurate. In this particular trip, the gas engine runs continually such that gas is continually consumed. How does one calculate the overall fuel economy, or distance travelled per unit of fuel consumed for the trip? In the absence of any other information, one could simply record the fuel economy at each second of the trip and take the average of these numbers to gain a pretty good estimation.

But now suppose that the road has a hill such that the car uses no fuel for a certain amount of time (perhaps it shuts off the engine and coasts or else uses the electric motor). In this case, the fuel economy for this section is infinite: there is a positive distance travelled $d$ but no fuel consumed $c$, so $f_e = d/c = d/0 \to \infty \; as \; c\to 0$. If we then use the method above for determining fuel economy for the whole trip, we find that there is infinite economy. But this is not so: a finite amount of fuel was consumed during the trip in total, which proceeded a finite distance, meaning that the true economy must be finite.

The problem here is the introduction of the infinite quantity. The system is no longer additive once this occurs, and therefore one cannot use fuel economy at each time point and add them together for an accurate measure of total economy.

Infinite sets are self-similar

Nonlinear maps often yield self-similar fractals if bounded. Here is a reason as to why this is: if we accept that nonlinear transformations are generally decribed by infinite sets, and that $A \in A$ (proper subset) is true for any infinite set, it necessarily follows that some subset of a map of a nonlinear transformation is equal to the entire set.

From this perspective, self-similarity is a consequence to any non-linear transformation. Particularly interesting is non-trivial self-similarity, which may be defined as scale invariance of a non-differentiable object (which can be discontinuous, like a Cantor set, or continuous with a non-differentiable border like a Julia set). Another definition for non-trivial self-similarity is that this is a scale invariance leading to an arbitrary amount of information at an arbitrarily small scale.

Self-similarity in either case can be thought of as a form of symmetry: it is the symmetry of scale. Unfortunately this symmetry is not necessarily helpful for computation.

Infinite recursion in self-similar transformations

The images of fractals on this site are examples of recursion without a base case (sometime called basis case). In the natural numbers with addition, 1 is the base case for which succession acts to make all other numbers. A recursive base case is the smallest indivisible unit.

For nonlinear transformations that yield fractal objects, there is no recursive base case because there is always a smaller part of the image at any scale that is equivalent to the entire image. For this reason, none of the fractal maps presented elsewhere on these pages are entirely accurate, because they must contain a base case in order to be computed.

Nonlinearity and problem solving

Nonlinear systems are not additive (see above), meaning that they cannot be broken down into parts and re-assembled again. As we have seen for fractals, attempting to isolate a small portion of a nonlinear map may simply lead to the presence of the entire map in miniature.

Now this is a serious challenge to any attempt to understand nonlinear systems because so much of human thought (or at least current problem solving thought) operates by the principle of additivity. For example, if one builds a house then the a foundation is made, the walls go up, and the roof is set. Or if a computer program is written, each individual variable is defined and operations are enumerated. The same is true of many disciplines of knowledge: smaller pieces are added together to make the final outcome.

In the models of nonlinear equations on this webpage, computer programs were used to represent the behavior of various nonlinear transformations. These programs work by dividing each problem into smaller versions of the same problem until a finite case is reached. For example, a program that observed the behavior of a particle over time first divides the time period into maybe 500000 individual time steps and then proceeds to calculate the behavior as if each time step were itself indivisible. Or perhaps we wish to understand which points in the complex plane diverge to infinity and which do not: in this case a certain resolution for the plane, perhaps 1400x2000, is chosen and then the maximum number of iterations is specified such that the program eventually halts.

In either case, the program generates (albeit high-resolution) approximations of the actual object. These objects are necessarily approximations, as any machine that attempts to produce an exact self-similar object (Julia set or anything similar) requires recursion without a base case, and this program will never halt. This is why Turing’s construct of a machine $T(a, a, x)$ never halts, ie the search for a solution to the problem ‘Does a Turing machine with the input $a$ as the program it runs on halt at time x?’ is undecidable inside the system because there is no recursive base case.

Sensitivity to initial values as implied by self-similarity

Self-similarity here is defined to mean an invariance with respect to scale.

Aperiodic dynamical systems are typically self-similar if bounded. From the definition above, this means that a small potion of the output of the dynamical system (for many inputs) resembles a larger portion of the output in some way or another.

Aperiodicity is implied by sensitivity to initial values, meaning that two points arbitrarily close together (but not located in the same place) in a starting region (phase space or any other area) will eventually diverge such that they are arbitrarily far apart, at least within the confines of the bounded region of the function image.

Self-similarity is usually applied to the dyamical system output, but sensitivity to initial conditions can be understood as self-similarity of input distance with respect to output distance. In other words, the distance between two points $p_o, q_o$ in the image space is invariant with respect to the scale of the distance bewteen initial points $p_i, q_i$. This implies a self-similarity in the system input (ie function pre-image) with respect to the outputs. Thus not only is the output self-similar with respect to itself, it is also self-similar with respect to the input with regards to distances between initial points $p_i, q_i$ and final points $p_o, q_o$.