Continuity and Poincaré-Bendixson

For this page, aperiodic signifies dynamical systems that are bounded (ie do not diverge to infinity) and lack periodicity. Specifically, continuous phase space portraits of differentiable ODEs are considered, so the trajectories of such systems are necessarily differentiable (as they are defined on differential equations). Unbounded dynamical systems may also be thought of as being aperiodic but are not considered. On this page but not elsewhere, a ‘map’ is synonymous with a ‘function’. ‘dimensions’ are taken to be plane dimensions.

Why discrete but not continuous maps in 2 dimensions exhibit fractal attractors

As seen with examples on this page, movement from a continuous to a discrete-like map of continuous equations in phase space mapping $\Bbb R^2$ into $\Bbb R^2$ results in a shift from a point to a fractal attractor. Note that these examples are only approximations of continuous maps, as in most cases one requires an infinite number of mathematical operations to produce a true continuous map of a nonlinear equation.

There is a good reason for this shift: the Poincare-Bendixson theorem, which among other findings states that any attractor of a continuous map in two dimensions must be periodic: the attractor is either a point or a circuit line, corresponding to a zero- or one-dimensional attractor.

The Poincaré-Bendixson Theorem: continuous dynamical systems in two dimensions are periodic

If continuous maps may form aperiodic attractors in three or more dimensions, why are they unable to do so in two or less?

A two dimensional curve’s intersection with a line may be discontinuous as well. Why can’t two dimensional continuous dynamical trajectories also be aperiodic? The answer is that though the intersection may be discontinuous, it is restricted over time because trajectories are unique in phase space (ie lines cannot cross).

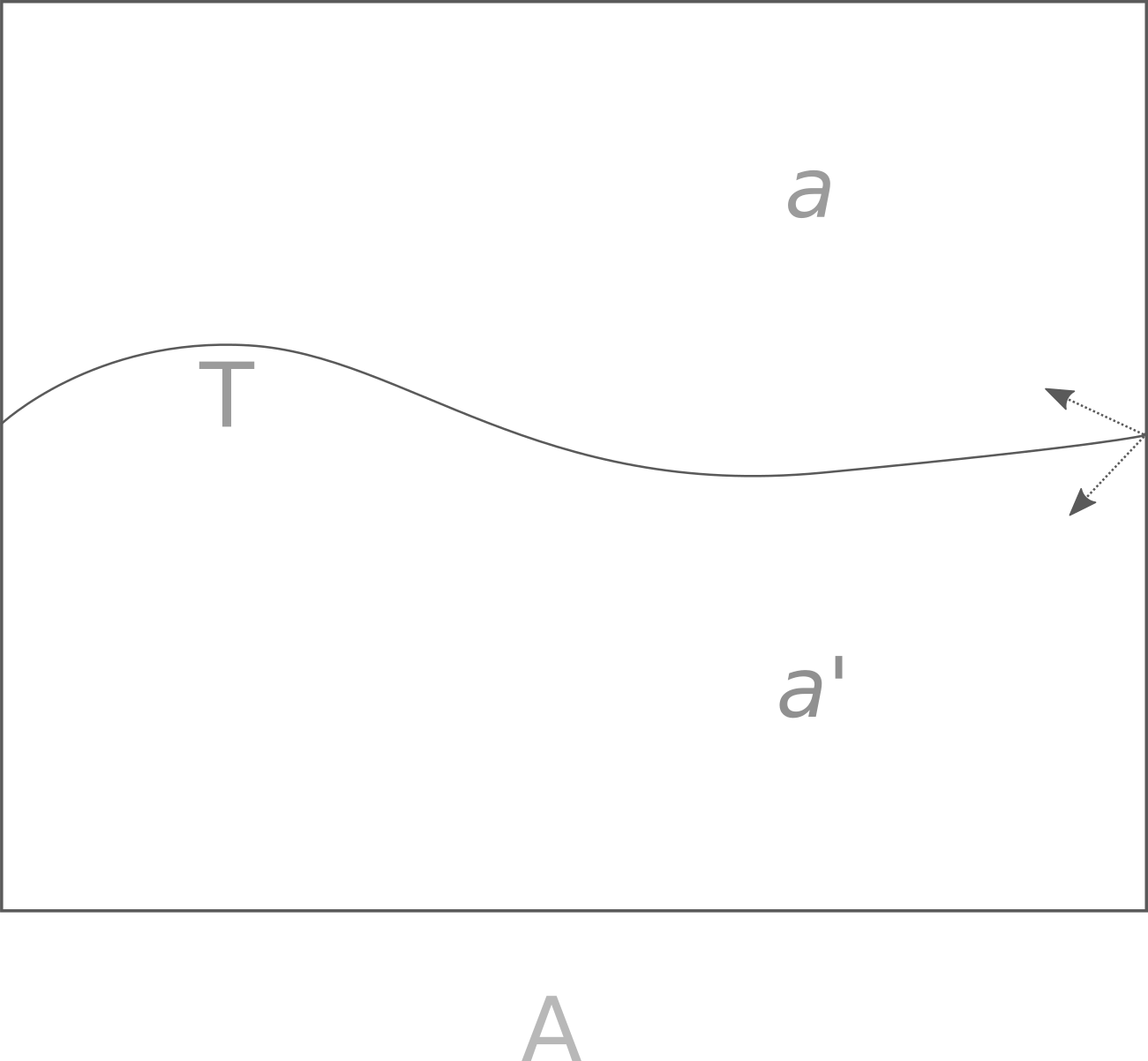

Here is a geometric argument: suppose a bounded trajectory passes through an arbitrary area $A$ of phase space in $D=2$, perhaps in $R^2$. Reaching the edge of $A$, the trajectory can eventually explore one or the other area $a$ or $a’$, because the trajectory is bounded and must change direction eventually.

(1)

(1)

Whichever of $a$ or $a’$ the trajectory enters, it is unable to cross into the other if moving through $A$. This is not necessarily the case if the trajectory exits $A$ and then re-enters. As the boundary region $R$ of the trajectory is finite by definition, exit and re-entry into $R$ is impossible.

We can fill $R$ with areas $A_1, A_2, A_3 …$ none of which are necessarily congruent with $A$. Some of $A_1, A_2, A_3 …$ necessarily share a border with $R$ because the latter has finite area. At these areas, the choice $a, a’$ restricts all future trajectory locations because exit from $R$ is not allowed. Now note that the trajectory is defined as continuous and differentiable, meaning that if $A$ is small enough then the trajectory path approximates a line. Therefore (1) is general to any arbitrary point in $R$, and future trajectories are restricted to either $a$ or $ a’$ and $R$ shrinks. As $t \to \infty$, $R \to 0$ and a trajectory’s future values are arbitrarily close to previous ones, meaning that the trajectory is periodic. More formally, the result is

\[D=2 \implies \\ \forall f\in \{f_c\} \; \exists n, k: f^n(x) = f^k(x) \; if \; n \neq k\]To see why this theorem does not apply to instances where $D=3$, observe that if another dimension is present, a bounded trajectory is not limited to $a$ or $a’$ but can exit the plane and re-enter an abitrary number of times in either. This means that $A$ is not restricted over time, and therefore the trajectory is not necessarily periodic.

Note also that this does not apply to a nowhere-differentiable map. Such a map is undescribable by ordinary differential equations regardless.

Postulate: $D-2$ dimensions are required for unrestricted, discontinuous cross-sections

For continuous maps, aperiodic attractors seem to form in $n-2$ dimensions. For the case of a 2-dimensional map considered by the Poincare-Bendixson theorem, this means that the aperiodic trajectory forms in 0 dimensions, ie at a point. As a point is by definition a period 0 attractor in phase space, there is no aperiodic trajectory in 2 dimensional phase space.

Note that this only applies to phase space in which every trajectory must be unique. Boundary maps of continuous ODEs are unsrestricted are capable of forming fractals in 2 or fewer dimensions.

Discontinuous maps may be aperiodic in 1 or more dimension

In other pages on this site, it was made apparent that moving from a continuous to a discontinuous map is capable of transforming a periodic trajectory to an aperiodic one. From the Poincaré-Bendixson theorem, it is clear why this is the case: a restriction to any space as seen above is impossible if the trajectory may simply discontinuously pass through (jump through) previous trajectories.

Careful observation of discontinuous 1-dimensional or 2-dimensional maps shows that trajectories cross each other if the map is aperiodic, or at least they would if the trajectories were continuous. The meaning here is not that one point in phase space heads in two directions (as this would no longer be specified by a function) but instead that if one connects each individual point in succession according the the order in which they are plotted, the connecting lines must cross each other if the map is aperiodic. An example of this was seen for the clifford attractor, where the map became aperiodic precisely when the trajectories crossed each other.

On the other hand, the pendulum map iterated discontinuously is eventually periodic. This is because the pendulum map trajectories do not cross each other. Therefore the available phase space shrinks as time passes. This means that this map is not aperiodic (for all time), and thus is insensitive to initial values.