Masked Mixers II

We continue exploring topics from Part I, with a more thorough version of these results found in this paper Application of masked mixers to larger datasets will be explored, theory is expanded, and the nature of the learned structure of masked mixers versus transformers is investigated.

Why Masked Mixers?

In Part I the motivation behind masked mixers for language modeling was detailed, but can be restated briefly: from high-dimensional projection theory (specifically the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma) we can accurately represent points in high-dimensional space in a space with much fewer dimensions (approximately the log of the number of points we have). This is an important result here because it implies that one can make language models that are capable of fitting extremely large datasets with what is currently considered an extremly small number of parameters: for example, a dataset one million times the size of the already large 15 trillion token Llama-3.1 dataset ($1.5 * 10^{13}$ tokens to be precise) may be arbitrarily well fit by a 352-dimensional model, which would require around 100 million parameters for a llama-style generative model.

Empirically it appears that the current state-of-the-art model type (the transformer) trains much too slowly to achieve this feat in any reasonable length of time, and the best-performing models are typically trained on thousands of GPUs for many days. From other investigations on information transfer between model layers, we wondered whether an architecture that more accurately represents its inputs (the masked mixer) would learn more efficiently.

Restricting our investigations to a small dataset (TinyStories, ie short children’s stories written by ChatGPT) we found that although masked mixers are more efficient learners than the original GPT-style transformers for the task of causal language modeling, highly optimized and current transformers learn even more efficiently. On the other hand, masked mixers were found to be much more efficient for language retrieval which is expected from their superior input representation properties.

Accuracy and Flexibility

Even with these promising features, the question may be asked: why masked mixers? Before proceeding to further investigations on this architecture, it is worth considering what you get when you swap self-attention for masked convolutions.

Before masked mixers were first trained, it was found that these models give much more accurate representations of their inputs than transformers. In effect, this means that given an input, the information necessary to uniquely identify that input via gradient descent is retained throughout the mixer but not the transformer. It could be argued for or against the idea that this would be useful for language generation, and perhaps more convincingly argued that this is important for langauge retrieval. But accurate input representation remains a useful feature of mixers for a variety of applications.

Perhaps as important is the model architecture flexibility of masked mixers. From investigations into representation in vision transformers, it was apparent that vision transformers require each key component of their architectures: layer normalizations, MLPs, self-attention, and residual connections are all required for effective gradient propegation.

This can be tested more directly by simply removing each component and observing the training process. Ironically for an architecture introduced as ‘Attention is all you need’, self-attention is actually the only removable component (as long as it is replaced by some other trainiable inter-token parameters): removal of MLPs, layer norms, or residual connections results in very poor language model training with either a failure to minimize a loss function (even if MLPs are removed or replaced with attention) or else training becomes unstable (for removal of layer norms or residuals) and gradients spikes to infinity. The reason for this is that attention is a rather difficult transformation for gradients to propegate across, and this is important because it essentially fixes the architectures of models with attention to similar patterns, all requiring some form or other of the same components transformers have (layer norms, residuals, MLPs, ets.).

On the other hand it turns out that langauge training proceeds perfectly well but is slightly less efficient when layer norms are removed from the masked mixer architecture. Even on a relatively large and difficult dataset such as the fineweb-edu 10BT, a 16-layer masked mixer with no layer norms whatsoever does not experience any spikes in loss during training, provided that the learning rate is relatively modest (<20%).

It is interesting to note that this is not the case for residual removal: even relatively shallow models suffer severely from the removal of residual connections, transformer or mixer.

This means that the mixer is effectively much more flexible than the transformer, and can be modified to a much greater extent. This topic will be explored more in the ‘Linear mixer’ section of this page.

Masked Mixers make better Autoencoders than Transformers

The accurate input representation present in masked mixers suggests that these models retain more information from their inputs than is present in transformers. It appears that next token prediction does not require or indeed is not particularly benefitted by this increased information compared to the focus brought by attention, but it was hypothesized and subsequently observed that masked mixers are far superior retrieval models as this task would be expected to require more information.

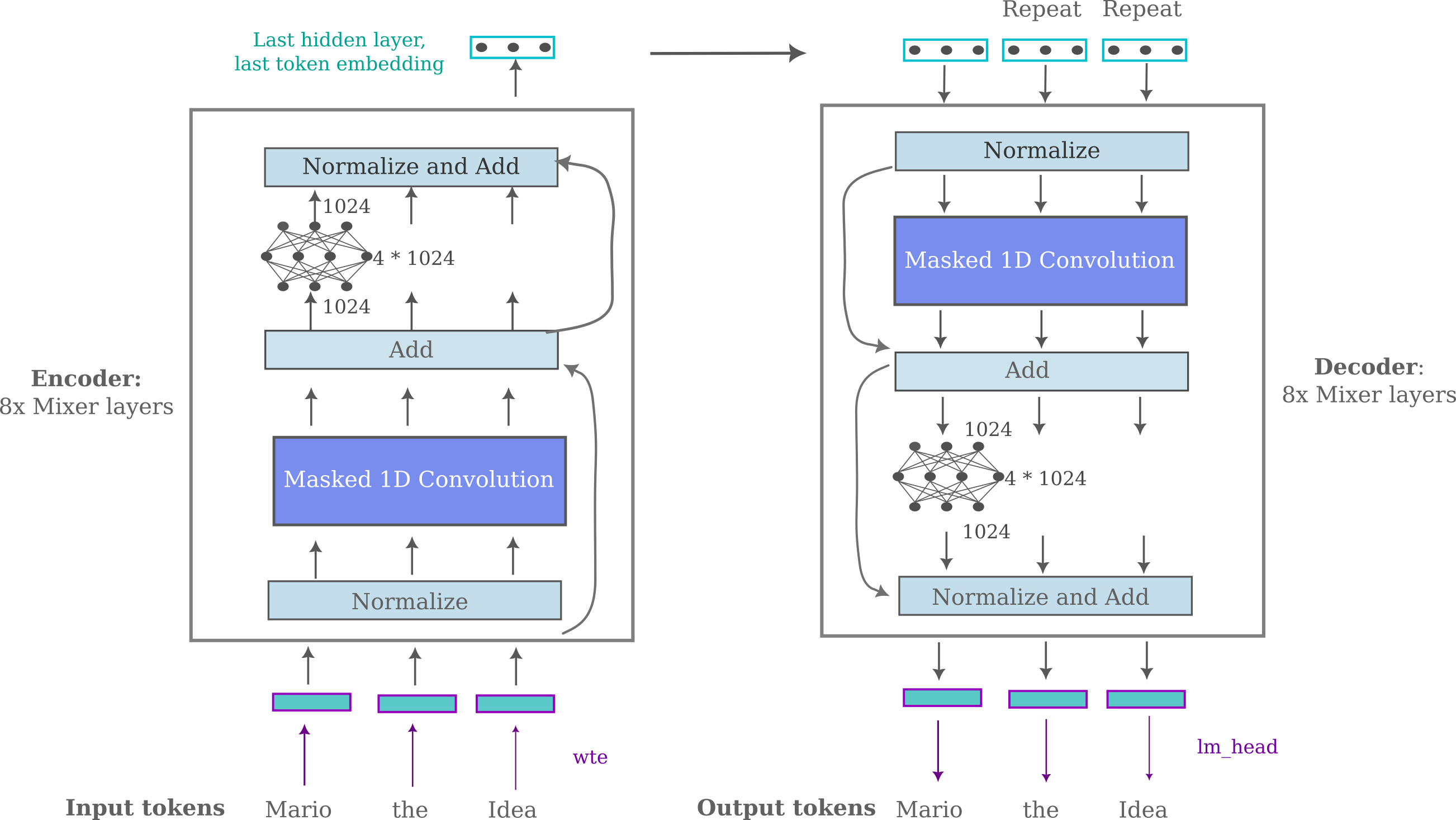

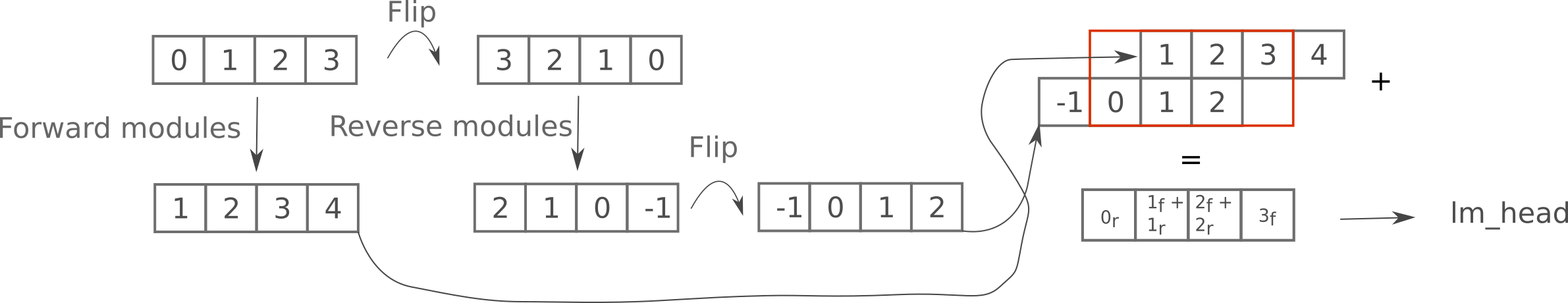

There is a perhaps more direct way to test the hypothesis that masked mixers contain more input information than transformers: we can modify the causal language modeling architectures of the masked mixer and transformer for the task of autoencoding an input. In particular, we want these models to learn a non-trivial autoencoding and not simply return each input token in the output. To do this we can use an encoder-decoder architecture but pass only the last hidden layer of the last token of the encoder to the decoder. For the masked mixer, this may be portrayed as follows:

This is perhaps one of the most direct ways to maintain the parallelization afforded by all-next-token training for a non-trivial autoencoder. For a masked mixer-based model, we can implement this by passing the inputs to the masked mixer blocks, obtain the last token’s last hidden layer vector values, repeat this embedding to the decoder mixer, and complete the forward pass. We don’t

class AutoencodingMixer(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None):

... # word-token eembedding

... # encoder blocks forward pass

encoder_embedding = x[:, -1, :].unsqueeze(1) # dim=[batch, token, hidden]

x = encoder_embedding.repeat(1, self.tokenized_length, 1)

... # decoder blocks foward pass

output = self.lm_head(x)

labels = rearrange(labels, 'b p t -> b (p t)')

output = rearrange(output, 'b t e -> b e t')

loss = self.cel(output, labels)

return loss, output

For an autoencoder version of Llama, there are a couple extra steps we need to take in order to preserve as much as possible from the original architecture while making the necessary modifications for autoencoding. First we need to overwrite the base model’s forward pass to avoid applying word-token embedding transformations (as we only want to transform tokens to embeddings once, not before each of the encoder and decoder stacks) and also avoid any transformations after the transformer blocks themselves. We can use either a LlamaModel (which does not contain the language modeling head) or the LlamaForCausalLM base class, and we choose the latter as that is the class we have used to train Llama models elsewhere on this page, and we are re-writing the forward pass regardless. This may be achieved as follows, where we supply the positional ids for each token and pass the inputs directly to the transformer blocks. We use this to initialize both the encoder and decoder modules.

class AbbreviatedModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, model, depth=8, tokenized_length=512):

super().__init__()

self.model = model

self.depth = depth

self.position_ids = torch.tensor([[i for i in range(tokenized_length)]]).to(device)

def forward(self, input_ids: torch.Tensor, **attention_mask: torch.Tensor):

# Matrix mult instead of embedding to prevent type incompatibility

x = input_ids

position_ids = self.position_ids.repeat(input_ids.shape[0], 1)

for i in range(self.depth):

x = self.model.model.layers[i](x, position_ids=position_ids)[0]

return x

Now we can combine encoder and decoder into the autoencoder model, applying the word-token embedding transformation before both modules and the language modeling head afterwards.

class AutoencodingTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_vocab, dim, encoder_model, decoder_model):

super().__init__()

self.wte = nn.Embedding(n_vocab, dim)

self.encoder = encoder_model

self.decoder = decoder_model

self.lm_head = nn.Linear(dim, n_vocab, bias=False)

self.cel = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

self.tokenized_length = tokenized_length

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None, attention_mask=None):

x = input_ids

x = x.to(device).squeeze(1)

x = self.wte(x)

x = self.encoder(x)

encoder_embedding = x[:, -1, :].unsqueeze(1) # dim=[batch, token, hidden]

encoder_embedding = encoder_embedding.repeat(1, self.tokenized_length, 1)

x = encoder_embedding

x = self.decoder(x)

output = self.lm_head(x)

output = rearrange(output, 'b t e -> b e t')

loss = self.cel(output, labels)

return loss, output

# initialization

configuration = LlamaConfig(**llama_config_kwargs)

encoder_model = AbbreviatedModel(LlamaForCausalLM(configuration), tokenized_length=tokenized_length)

decoder_model = AbbreviatedModel(LlamaForCausalLM(configuration), tokenized_length=tokenized_length)

model = AutoencodingTransformer(n_vocab, dim, encoder_model, decoder_model)

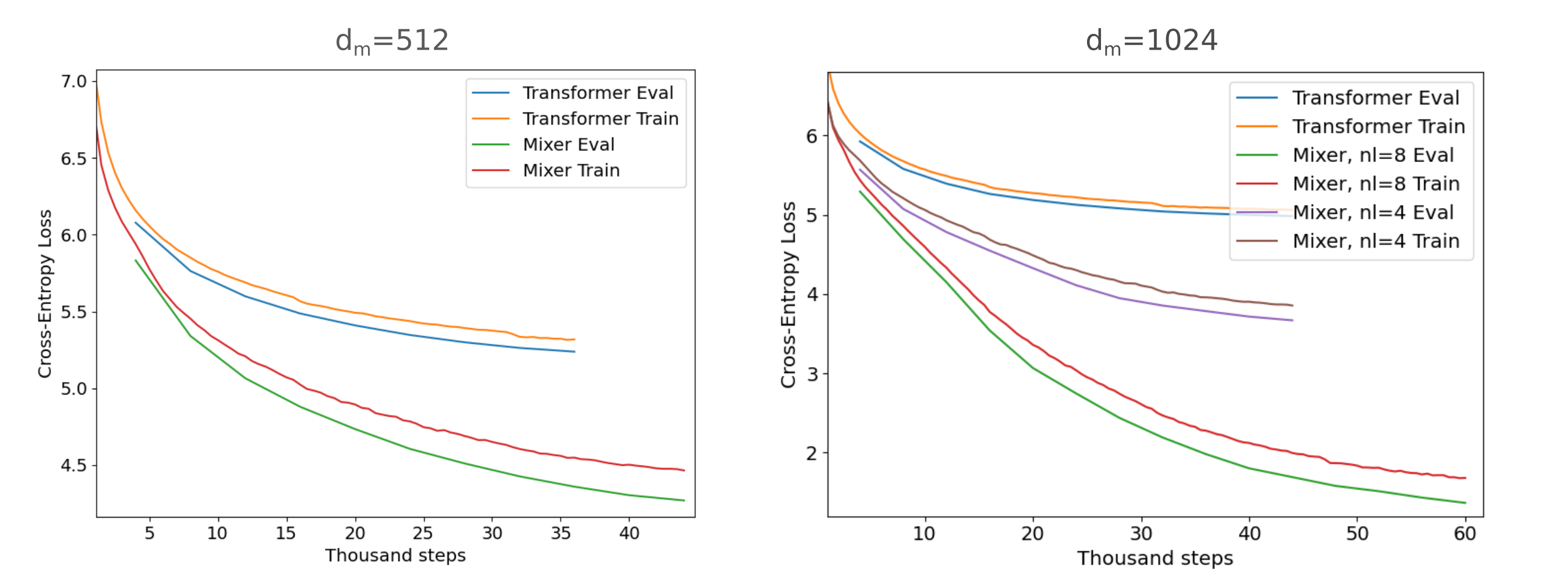

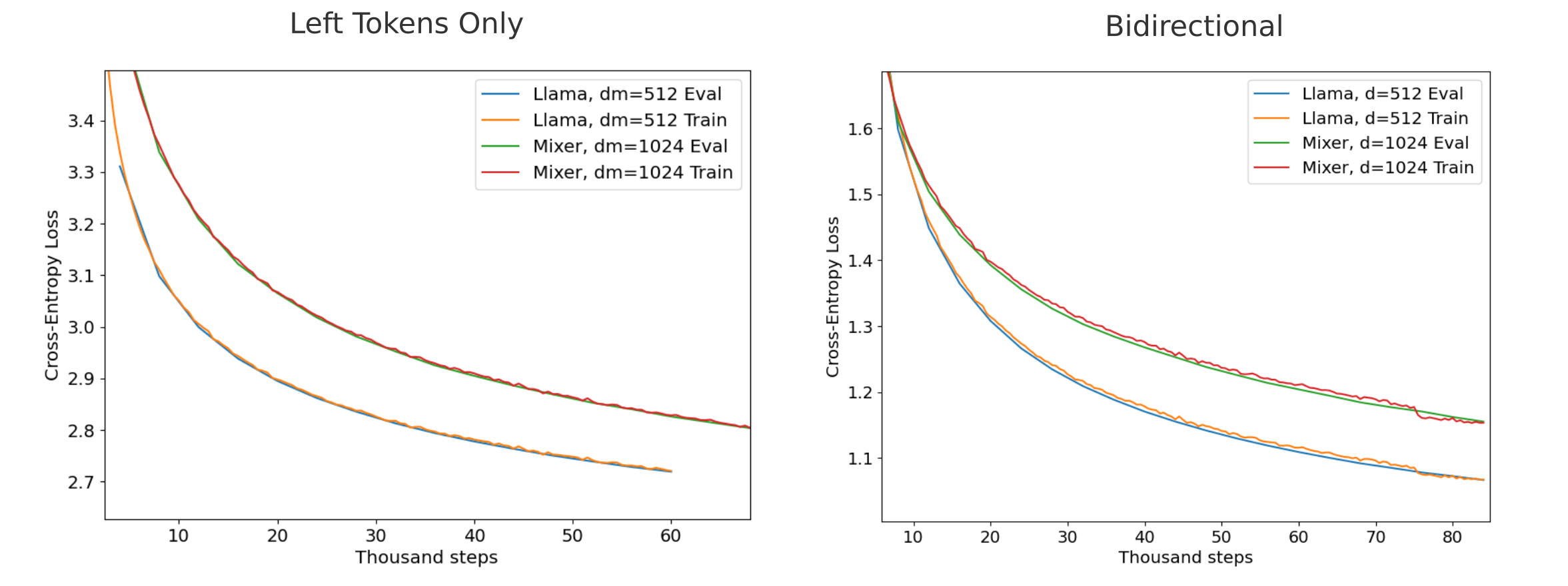

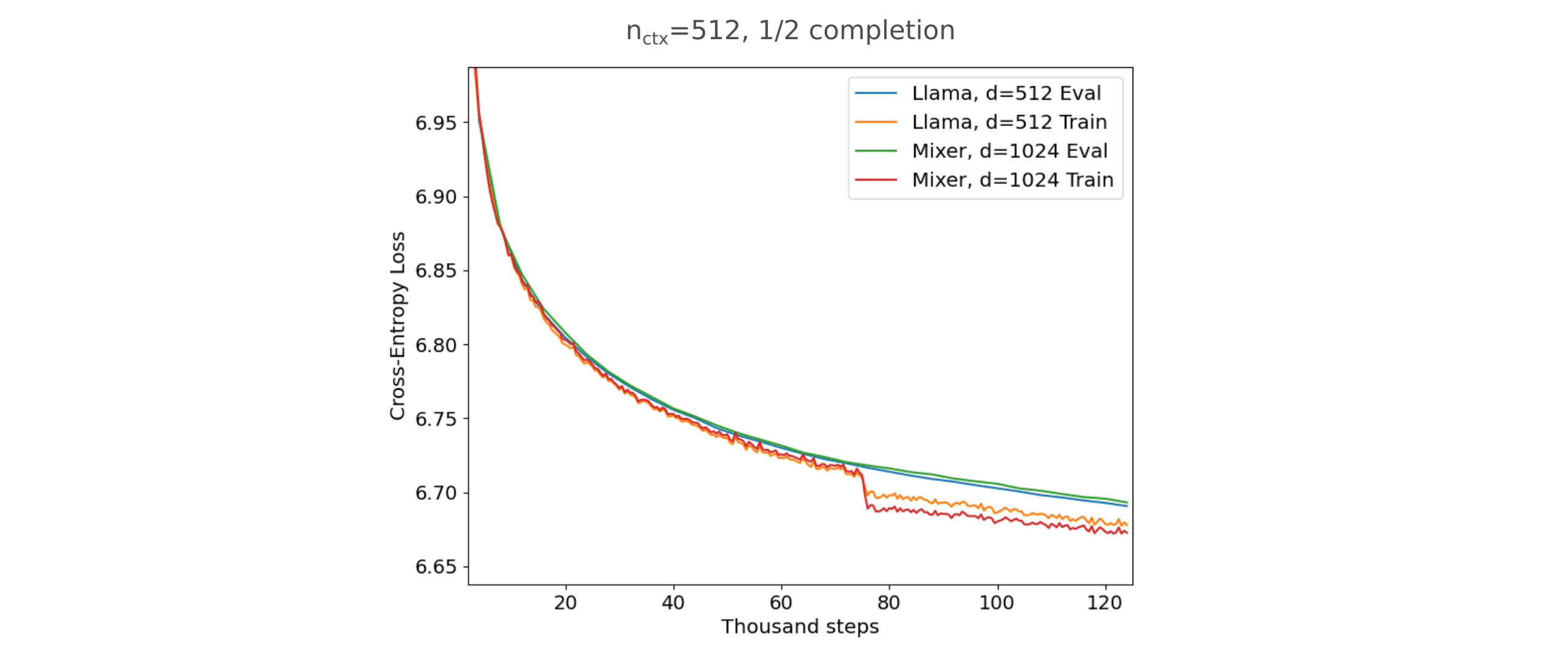

Recall that masked mixers contain far fewer inter-token parameters and thus may be trained with a much larger $d_m$ size while maintaining other architectural constraints identically to transformers for fixed memory, and mixers of identical architectural ‘sizes’ train much more quickly. With this in mind, we can first observe autoencoding performance for identically-sized models: given a $d_m$=512 and $n_l=8$ (ie 8 encoder layers and 8 decoder layers). After 2.25 hours of TinyStories training on the 4x V100 cluster, the masked mixer autoencoder reaches train/test losses of 4.53/4.35 respectively whereas the same-dimensional transformer only manages losses of 5.31/5.23. For $d_m=1024, n_l=4$ (the largest $d_m=1024$ transformer that fits in V100 memory) reaches 5.05/4.99 train/test loss after three epochs, whereas a masked mixer autoencoder of the same $d_m, n_l$ reaches 3.85, 3.66 (below).

These are very large performance gaps: recall that the difference between transformer and mixer CLM loss is typically 0.5-2%, such that with a modest increase in training duration one architecture is able to achieve the loss of the other. But from the figure below it is apparent that it would take a huge number of steps (perhaps 1000x) for the transformer to match the mixer’s loss achieved, if it ever is. The figure below provides the loss curves upon various training runs. Note that the 1024-dim mixer is more or less equivalent in memory and somewhat faster than the 512-dim transformer model, and that the mixers are trained with dropout ($p=0.05$) hence the drop in evaluation loss compared to training loss at all steps.

The gap is even larger when we consider that the mixer occupies a much smaller memory footprint for identical $d_m, n_l$ parameters. If we match the mixer to the $d_m=1024, n_l=4$ transformer’s memory on device by doubling the $n_l \to 8$, the mixer reaches 1.65/1.37 train/test loss using the same compute (4x V100s, 6h) as the above transformer. This would be expected to require thousands (!) of epochs for the transformer to match, and in that way one could claim that the mixer is hundreds or thousands of times as efficient an autoencoder as a transformer. It would be expected that the masked mixer would be a better autoencoder than a transformer because of its bias towards invertibility, but the performance gap here is remarkable nonetheless.

Fineweb Causal Language Modeling Efficiency

The goal of a machine learning algorithm is to minimize some loss function on a dataset efficiently, and the hope is that the minimization process and dataset are sufficient to generalize to the task you actually want to perform (typically representation by a ‘test’ or ‘evaluation’ dataset). The choice of a loss function, the model architecture to use, the optimization approach, the amount of compute employed, and the dataset are all important factors in whether the generalization actually occurs.

In Part I this question was addressed for two model architectures on a relatively small language dataset composed of synthetic one-paragraph children’s stories written in the vocabulary of a four-year-old. There it was found that masked mixers are nearly as efficient language modelers as transformers for next token generative tasks, and far more efficient retrieval models.

It may be wondered just how generally applicable these results are: perhaps mixers with their relatively simple inter-token linear transformations are effective modelers of TinyStories because that dataset is itself extremely simple? If this were the case then one would expect to find that the masked mixer is much worse than modern, optimized transformers for causal language modeling on more complex datasets.

This hypothesis must be taken seriously because lack of correspondence of model training from a very small and self-contained dataset to larger ones is somewhat common in the deep learning field. Examples abound of model architectures that effectively modeled small datasets but were found to be relatively inefficient for large ones. Notable vision model cases are the variational autoencoder, which models MNIST well but is not powerful enough to train efficiently on ImageNet, and the Generative Adversarial Networks that model small and medium-sized datsets with some training instability but suffer from more frequent training instabilities upon application to larger and more varied datasets. As a counterpoint to those examples, it should be noted that GANs (and to some extent VAEs) are generally more efficient and flexible modelers of very small datasets (MNIST etc.) compared to diffusion models, but the latter have proven to be much more effective for large datasets.

Applying masked mixers and modern transformers to larger, more difficult datasets with more compute can give us an indication whether the masked mixers would or would not be efficient general language learners. The fineweb-edu dataset is particularly well-suited to this kind of test, as it is an extensively curated dataset containing a wide variety of text that has been shown to be capable of training large language models more efficiently than less-curated datasets. Specifically, this dataset began as a compilation of the Common Crawl, underwent multiple rounds of filtering via LLMs for quality and then educational content and finally deduplication. This dataset is designed to be similar but somewhat more efficient than (proprietary) datasets used to train Mistral and Llama models, and can in that respect be considered to be much more difficult to model than TinyStories. We use the 10 billion token (GPT2 tokens, that is) subset of the fineweb-edu dataset so that our relatively small models may be trained in a reasonable amount of time on a single 4x V100 compute node.

The primary challenge of training a model on a large dataset like this (versus a small one) is that the larger the datset, the less likely it can be stored in memory for fast access during batched forward and reverse passes during training. To see why this is, observe that each token is usually stored as a torch.long = torch.int64 datatype, meaning that each token requires eight bytes. A ten billion token dataset would therefore be expected to require around 80 GB of memory, and for distributed data parallel training each GPU requires its own dataset by default (although this could be modified if necessary). Thus we can expect to require 320 GB for a four-GPU system, which is currently a little more than the node used here contains.

One option would be to simply increase the existing server’s memory (more than one terabyte of memory can be installed in this machine) but that is a temporary solution, as any dataset larger than this memory value will experience the same problem that we are meeting with the fineweb-edu. Very large datasets may be streamed directly from storage in the cloud (an S3 bucked or Azure Blob, for example) such that a local machine never stores more than a fixed amount of an arbitrarily large dataset, but this approach is heavily bandwidth-dependent. In the author’s experience streaming large datasets lead to poor GPU usage for training smaller models, where the forward and reverse passes do not provide enough time to load a batch of data over the network without subsequenty delays. Instead, we can use clever data loading algorithms to load training and test data from storage into memory and back again during the training process, a process analogous to streaming the data from disk to CPU memory, and thence to GPU memory. Modern solid state drives read and write contiguous data at speeds of 500-5000MB/s, which is much faster than one will typically see for network streaming (which does typically not match one’s internet bandwidth).

With this approach settled on, there are a number of subsequent design considerations to make: for example, do we want to load only the text from storage and tokenize each batch before sending the tokens to the GPUs, or do we want to tokenize ahead of time and simply load the tokens directly and send these to GPUs? Some quick testing is enough to show that tokenizing large batches (say $n=128, n_{ctx}=1024$) leads to poor GPU allocation and delays in data processing, so we take the latter approach. We make use of the HuggingFace datasets library, which implements datasets as PyArrow (python bindings for the C++ Apache Arrow libs) tables. This library is handy for fast loading from disk, and was chosen as it is well-integrated with the fineweb-edu dataset schema without too many modifications for most tasks.

Before proceeding with dataset examination, it is worth noting that we want to train a tokenizer on this new dataset. For the TinyStories work in Part 1, we trained a Llama-style tokenizer huggyllama/llama-7b available on the Huggingface Hub. This tokenizer was quickly found to be unsuitable for a dataset as large as the Fineweb as it uses normalizations and other computations that make it train (the process of adding new tokens to the original set via finding the most common pair of that set of tokens in the corpora) extremely slowly, so we instead switch to the official Llama 3 tokenizer meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B and retrain on the Fineweb, which takes hours rather than days.

fineweb-edu 10BT is composed of approximately 10 billion tokens distributed across around 90 million examples. In the following code snippet, we use batch encoding to store the first 1024 tokens of each of these examples (padding where necessary) using the datset.map() functionality.

Let’s examine a random sample of the fineweb-edu 10BT dataset. This dataset is stored as an Arrow table, and upon calling the datasets.load_from_disk() or load_dataset utility each row of this table may be represented Python dictionary. Below is one such sample (the text is truncated for brevity). Here we can see the 'text' itself, a universally unique identifier for this sample ('id'), the actual source 'url', the Common Crawl dump source 'dump', and the path to the file’s cloud storage ('file_path'), the 'language', a number of measurements determining the quality and educational content of this text ('language_score', 'score', 'int_score'), and the number of (GPT2) tokens in the text.

{

'text':['Researchers from the United States and Switzerland have developed mathematical and statistical tools for reconstructing viral populations using pyrosequencing, a novel and effective technique for sequencing DNA. They describe their findings in an article published May 9th in the open-access journal PLoS Computational Biology.\nThe scientists knew that pyrosequencing reads are short and error-prone, and thus set out to improve upon this process...'],

'id': ['<urn:uuid:b3a05e48-160f-424f-8545-119be2db0560>'],

'dump': ['CC-MAIN-2017-26'],

'url': ['https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-05/plos-ncm050808.php'],

'file_path': ['s3://commoncrawl/crawl-data/CC-MAIN-2017-26/segments/1498128320270.12/warc/CC-MAIN-20170624170517-20170624190517-00112.warc.gz'],

'language': ['en'],

'language_score': [0.846785843372345],

'token_count': [609],

'score': [2.71875],

'int_score': [3]

}

We want to tokenize the text, but don’t necessarily care about the metadata. Perhaps the fastest approach is to tokenize the text in batches, truncating samples that are too long and padding those that are too short as follows

def tokenization(example):

tokens = tokenizer.batch_encode_plus(

example['text'],

add_special_tokens=False,

return_tensors='pt',

truncation=True,

max_length=1024,

padding='max_length',

padding_side='right'

)

return tokens

where we use the dictionary lookup example['text'] to access the text. We can then perform a train/text split of the dataset and add the tokens to the dataset via batched dataset.map() with the tokenizer above, and save the resulting tokenized dataset to disk in the desired location.

import datasets

from datasets import load_dataset, load_from_disk

def tokenization(example):

...

def map_dataset(text, path):

dataset = text.map(tokenization, batched=True)

dataset.save_to_disk(train_path)

return

if __name__ == '__main__':

train_path = "/path/to/store/training/tokens"

train_path = "/path/to/store/test/tokens"

dataset = load_dataset("HuggingFaceFW/fineweb-edu", split="train", name="sample-10BT", streaming=False)

train_data, test_data = dataset.skip(split_index), dataset.take(split_index)

map_dataset(train_text, train_path)

map_dataset(test_text, test_path)

If desired, one can remove the unneeded keys from each dataset entry (columns in Arrow format) by using a dataset.map() that iterates through each example’s keys, deleting all that are not required.

The method above works well for higher-context (512 and 1024) entries but leads to too many tokens being removed when smaller context windows (<512) are required. In this case, we cannot use batched tokenization examples are typically of different lengths: instead we perform unbatched tokenization without truncation followed by reshaping such that each sample has len(tokens) // n_ctx tensors each with n_ctx tokens. What we are doing here is to split up each example’s sequence of tokens into a batch of many sequences tokens, discarding the last sequence if its length is less than n_ctx (which is faster than padding). The following example is called during map_dataset() via train_dataset = train_text.map(tokenization, batched=False) and the same for the test dataset.

def tokenization(example, n_ctx=32):

tokens = tokenizer.encode_plus(

example['text'],

add_special_tokens=False,

return_tensors='pt',

truncation=False,

padding=False,

).input_ids

tokens = torch.flatten(tokens, start_dim=0)

batch_size = len(tokens) // n_ctx

length = n_ctx * batch_size

tokens = tokens[:length].reshape(batch_size, n_ctx)

return {'input_ids': tokens}

Debatching the input is trickier than it sounds: we really want to convert each example into however many examples there are batches in that sample, which the datasets library does not natively support. Instead we can form an array of inputs (one for each batch sample in our example), convert the array to a PyArrow Table object and return that object to the mapper. The key to this approach is that dataset.map() only allows batched outputs if batched=True is specified in the mapper args, but we actually need a batch_size=1 (unbatched) input as each example is expected to have a different batch size than any other example. This can be implemented as follows: after the dataset is tokenized into batches as above, it is loaded and debatched and saved to a new dataset object as open datasets cannot be overwritten.

def debatch(example):

batch_size = len(example['input_ids'])

keys = list(example.keys())

debatched_inputs = [{'input_ids': tokens} for tokens in example["input_ids"][0]]

examples = pa.Table.from_pylist(debatched_inputs)

return examples

test_dataset = test_dataset.map(debatch, batched=True, batch_size=1)

train_dataset.save_to_disk(train_path + '-debatched')

Making use of datasets PyArrow objects is straightforward: first we use load_from_disk and then the datsets may be passed directly to the transformer.Trainer as follows:

train_dataset = load_from_disk(train_path)

test_dataset = load_from_disk(test_path)

...

trainer = transformers.Trainer(

model=model,

train_dataset=train_dataset,

eval_dataset=test_dataset,

args=training_arguments,

data_collator=transformers.DataCollatorForLanguageModeling(tokenizer, mlm=False),

)

Once this is done, we can observe model performance on the fineweb-edu! Some quick testing tells us some things that one would probably expect: firstly that this more difficult dataset requires much deeper models than TinyStories, as the latter was most efficiently modeled by 4- or 8-layer mixers and transformers whereas the fineweb-edu is most efficiently modeled by 16 (or more) -layer models. We mostly stick to 16-layer models, as these are the deepest that for reasonable $d_m$ layer widths (batch size of 128 or larger) such that fineweb-edu 10BT is trainable in under one day on a 4x V100 node. We find that $d_m=1024, n_l=16$ mixers train in approximately the same time and memory per step as $d_m=512, n_l=16$ Llama-style transformers (4-headed) that are otherwise optimized for minimum loss per given compute.

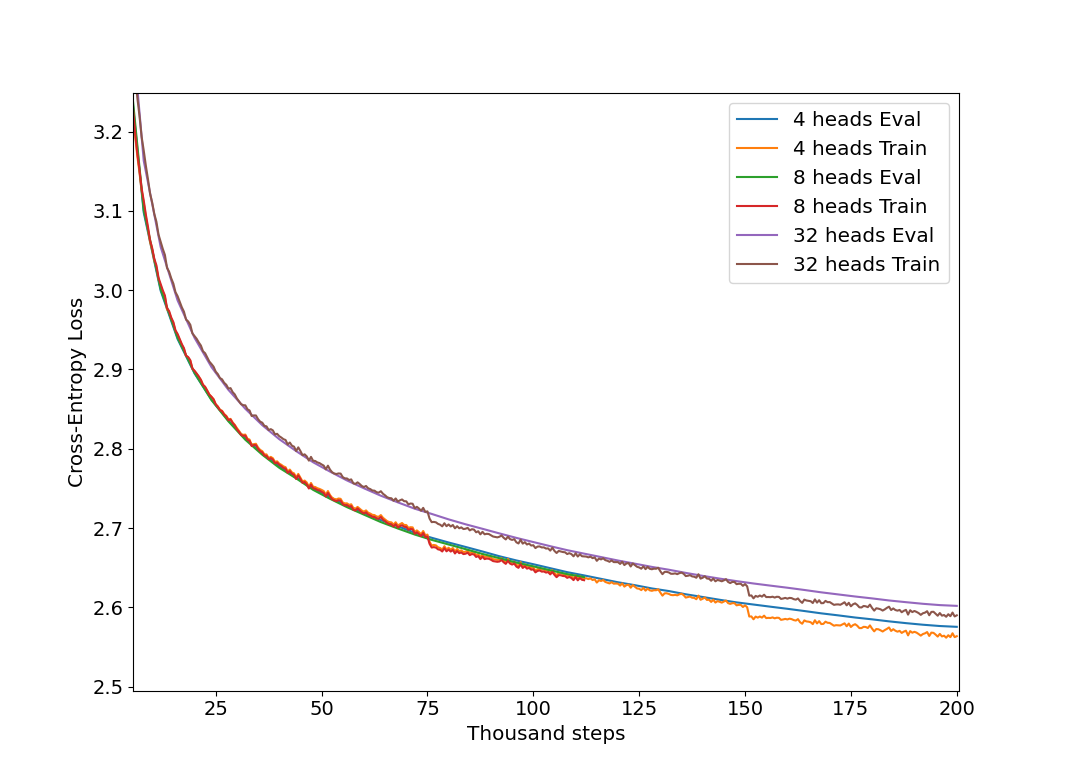

It should be noted that using only 4 heads is somewhat unusual in training models today, as the default Llama head number is much larger at 32. This number was initially chosen because it was found to be optimal for TinyStories training, and after testing we see that it is also optimal for fineweb-edu as well: in the following figure, we can see that a four headed llama learns virtually identically to an 8-headed model on a per-step basis, and somewhat more efficiently than a 32-headed llama (all models have $n_l=16, d_m=512$). Increasing the number of attention heads leads to a significant decrease in the number of samples trained per second, such that on a per-compute basis the 4-headed llama is most efficient.

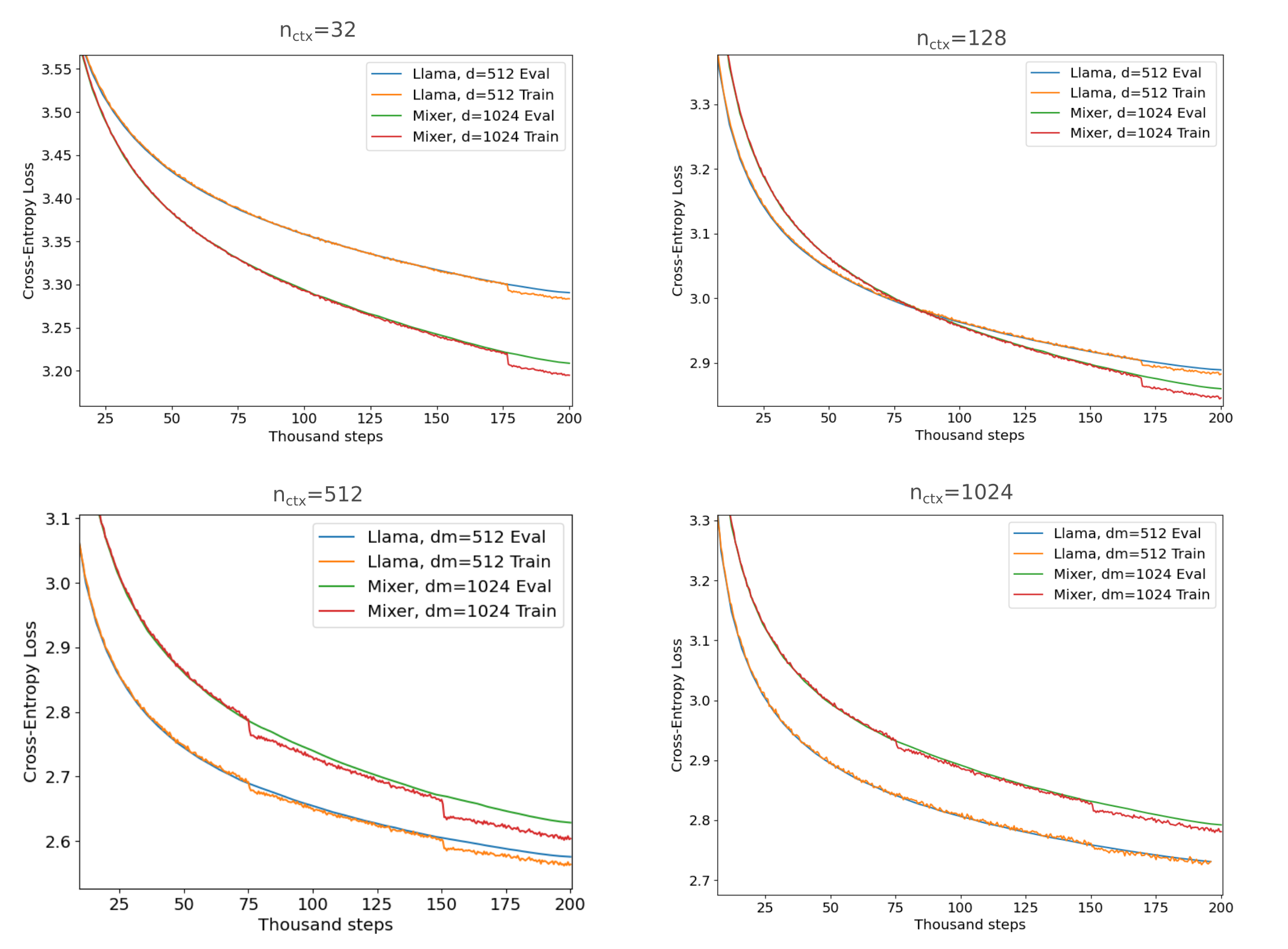

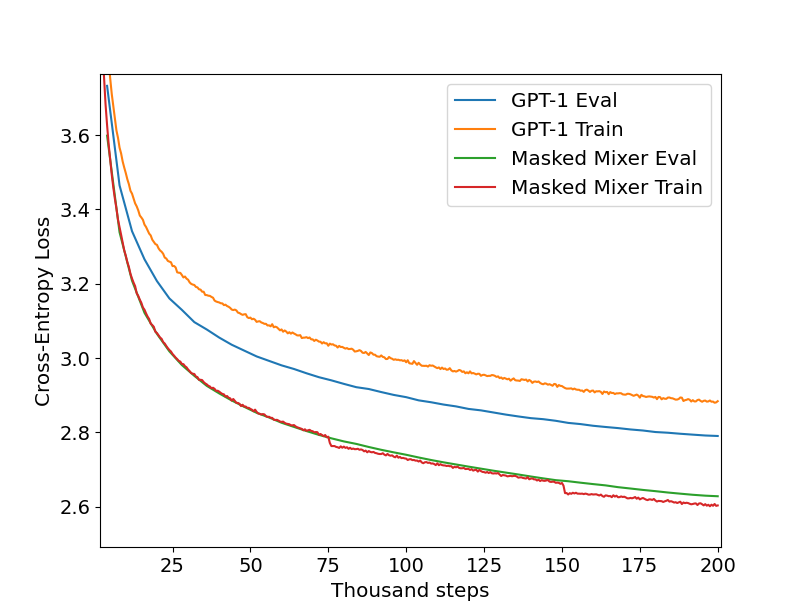

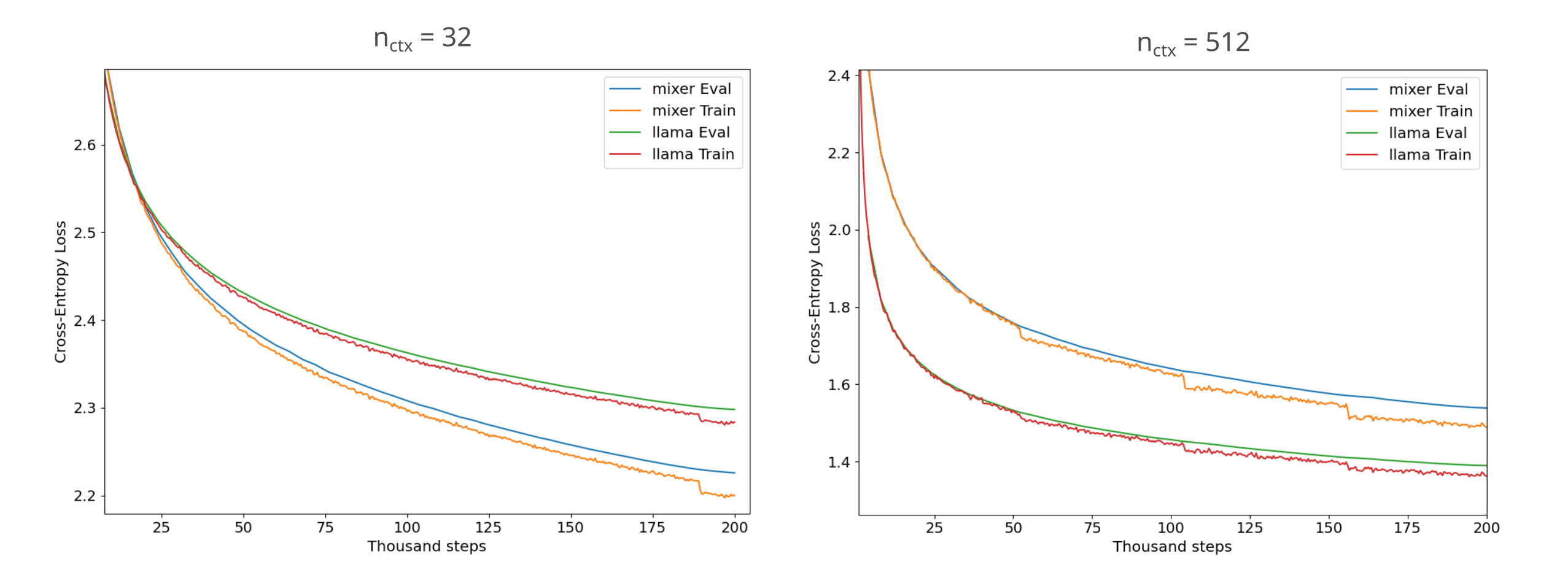

Loss curves during masked mixer and transformer training on fineweb-edu 10BT are given below, where each training run requires approximately 20 hours on the 4x V100 (batch sizes are modified to maximize memory usage such that $n_{ctx}=32$ samples are trained with a total batch size of $4* 512 = 2048$, $n_{ctx}=128$ with batches of size $4* 128 = 512$, and $n_{ctx}=512$ with batches of size $4*32=128$ etc). Here all model are $n_l=16$ layers.

There are a few notable observations from the above figure, the primary being the answer to the question posed at the start of this section that masked mixers scale just as well as, if not better than, transformers to large and difficult datasets. Recall that the loss gap between the most-optimized Llama model and masked mixer for language generation evaluation was 1.71 and 1.61 (a gap of 6%) for $n_{ctx}=512$. For the same $n_{ctx}$, we see a smaller gap (at 200k training steps or around 24 hours on 4x V100s, mixers achieve evaluation CEL of 1.63 versus transformers with 1.58, a difference of approximately 3%) corresponding to fewer extra training steps required to have the masked mixer’s accuracy match that of the transformer. Furthermore, for $n_{ctx}=512$ it is apparent that the gap between mixer and transformer loss narrows as training proceeds such that with more compute applied one would expect the masked mixer to be the more efficient architecture given the current constraints. This notion is supported by observing that $n_{ctx}=128$ models experience exactly this phenomenon of the course of their training, which uses 4x the batch size and thus 4x the number of samples that $n_{ctx=512}$ training does.

From earlier investigations we hypothesized that the transformer is a somewhat more efficient causal language model than the masked mixer because next token prediction is fundamentally a many-to-one mapping: we have many previous tokens and only get logits for one next token. This mapping mirrors the intrinsic properties of the transformer’s attention operation, where information from most inputs is removed during the forward pass. If this were the case then one would expect for next token prediction with fewer previous tokens (which is closer to a bijective mapping) to favor the masked mixer, and this is precisely what is found for $n_{ctx}=32$ or even $n_{ctx}=128$.

Masked Mixers outperform an early CLM Transformer on the Fineweb

Elsewhere it was found that masked mixers outperformed early transformer implementations for causal language modeling of a small and relatively simple langauge dataset (TinyStories). It may be wondered whether or not this is also the case for a much larger and more complex dataset such as the Fineweb, or whether an early transformer exhibits superior scaling properties compared to the masked mixer.

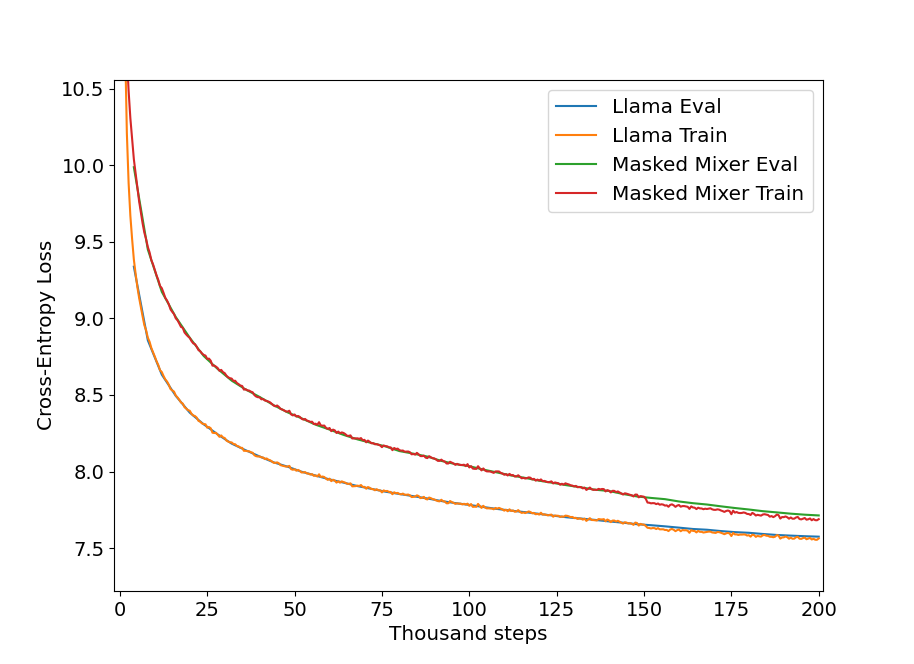

We can investigate this question by training a GPT-1 style transformer model using the same tokenizer, loss, and dataset as the masked mixer. We performed hyperparameter optimization and architectural tuning on a smaller dataset before applying GPT to this large dataset to ensure that the comparison between early transformer and masked mixer is valid. The results for the default context window $n_{ctx}=512$ with the largest batch sizes that fit in GPU memory (16GB x4 GPUs) are as follows:

From this we can clearly see that the masked mixer is more efficient for causal langauge model training than an early CLM-style transformer for a large and diverse dataset, suggesting that early transformer implementations do not in fact scale to larger datasets in superior ways to masked mixers.

Bidirectional Language Modeling

We have seen that attention appears to confer benefits to next token prediction, and theoretically this can be expected due to the many-to-one map inherent in this task as well as the inherent noise in real language (not every word necessarily follows from the last, but may be chosen at will). It may be wondered which of these two has a greater influence on the abilities of language models, a question that in this case may be rephrased as follows: is it the inherent noise present in language that is most responsible for the greater efficiency of transformers versus mixers in CLM tasks, or else is it simply the type of mapping performed which is many-to-one?

A simple way to start to address this question is to perform bidirectional language modeling. The justification for this is that with tokens present both before and after the token we want the model to infer, there is in some sense less inherent noise in the language in that there is a greater likelihood that a logical rule may be made to pick one and only one token than there would be if only left-side tokens are present. On the other hand, bidirectional modeling results in an even greater number of tokens that are mapped to a single token than CLM training (twice as many on average) and thus somewhat exaggerates the many-to-one mapping phenomenon. The idea is that if many-to-one mapping is the largest source of the transformer-mixer difference then the mixer will be comparatively worse at bidirectional language modeling than it was for causal language modeling, either reaching or exceeding transformer efficiencies. Conversely, if language noise is the major source of efficiency difference then mixer training efficiency would be comparatively better than for CLM tasks.

In causal language modeling sequence of tokens is used to predict one ‘next’ token, ie the token to the right for English text. There are other methods of langauge generation, however. In particular one can model language without any causal language masking, instead masking certain tokens themselves such that the task is essentially to infer these few tokens which is analogous to the grade school task of ‘fill in the blank’. This token masking approach typically proceeds by masking up to 15% of tokens in a corpus, and using the masked tokens’ identities as the labels, and this is the method for BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTa and other such model training.

It is straightforward to see that this is not a particularly efficient method of training, however: because only 15% of tokens are masked and inferred by the model, only 15% of tokens are trained on during each forward pass. Contrast this with the all-next-token training method for causal language modeling in which all tokens are trained upon each forward pass, and we can estimate that all-next-token training has approximately $1 / (5/33) = 33/5 = 6.6$ times the throughput of this traditional masked langauge modeling approach. This is not an easily ameliorated problem for masked langauge modeling, however, as if too many tokens are masked then the learned distribution becomes too far from the goal of inferring usually one or a few tokens at most.

To train more efficiently, we can instead mask no tokens while maintaining the all-next-token approach of causal language modeling, but apply this method in both the forward and reverse directions simultaneously with some careful tensor shifting. This means that every token is trained upon each forward pass, as each ‘next’ token is both ‘next’ in forward and reverse directions. There are a number of different methods to implement this idea, and as we will focus on two that require some care to do so. Firstly, we will examine a masked mixer implementation before proceeding to a Llama-style transformer.

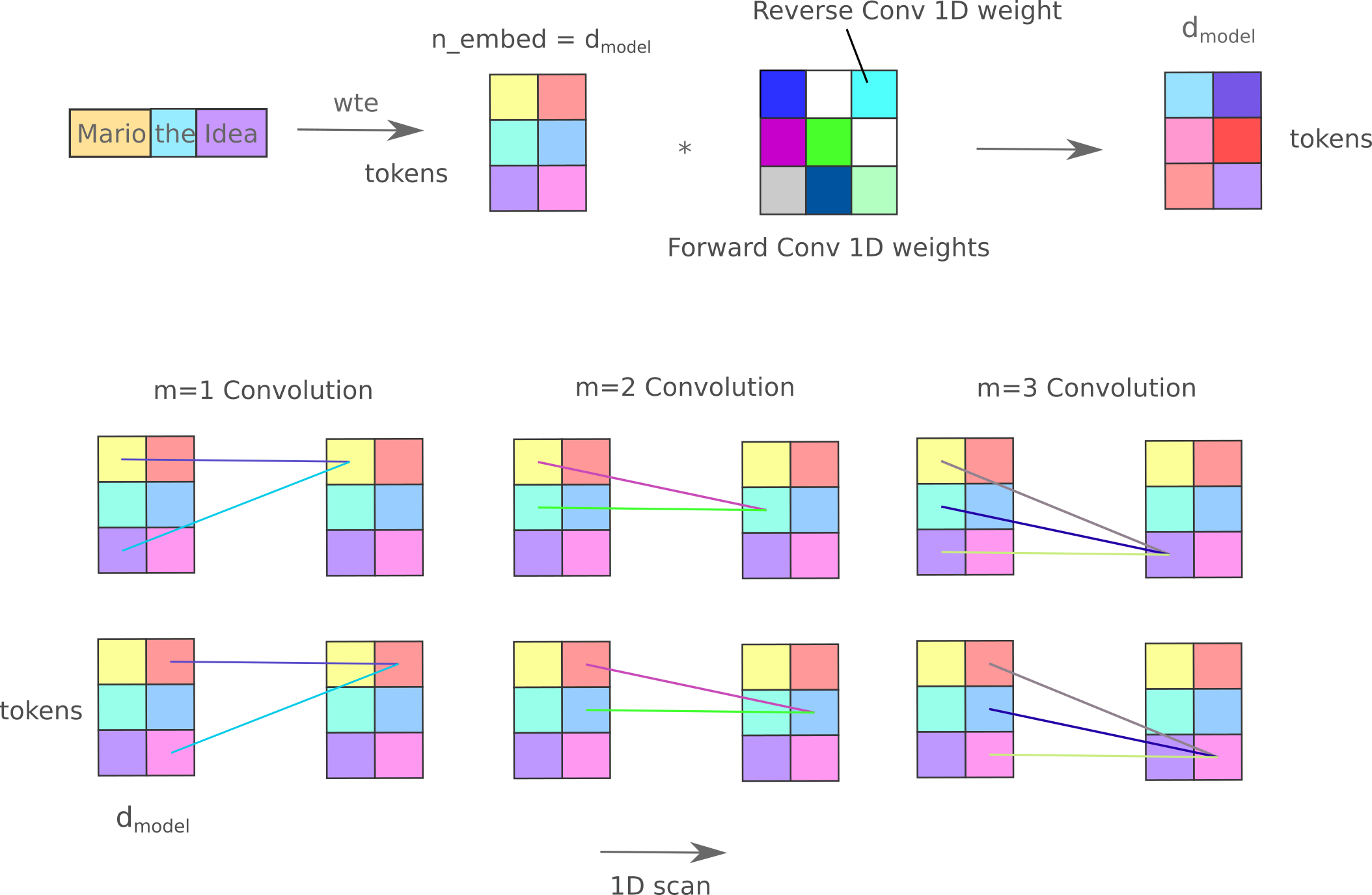

Recall that the causal language modeling masked mixer uses a lower-triangular mask on the inter-token convolutional weights to prevent information from right-indexed tokens from moving ‘backward’ and influencing next token prediction. We can use the exact same implementation for the ‘forward’ direction but as we now want information from tokens to the right of our predicted token (but importantly not that token itself) to be used, we can include convolutions with weights connecting tokens $t_{n+2}, t_{n+3}, …, t_{N}$ to $t_n$. Note again that $t_{n+1}$ remains masked, as this is the token we are attempting to predict. This can be depicted as follows:

A naive implementation of which (using two separate convolutional weight matrices rather than one for clarity) is

class DoubleMixerBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, length, clm_mask=False, expand_conv=False):

super().__init__()

self.patch_layernorm = nn.LayerNorm(dim)

self.seq_layernormf = nn.LayerNorm(dim)

self.seq_layernormr = nn.LayerNorm(dim)

self.dim = dim

self.length = length

self.patch_ff = FeedForward(dim)

self.convf = nn.Conv1d(length, length, 1)

self.convr = nn.Conv1d(length, length, 1)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor):

masked_convf = torch.tril(rearrange(self.convf.weight, 'f d p -> p f d'), diagonal=0)

self.convf.weight.data = rearrange(masked_convf, 'p f d -> f d p').contiguous()

masked_convr = torch.triu(rearrange(self.convr.weight, 'f d p -> p f d'), diagonal=2)

self.convr.weight.data = rearrange(masked_convr, 'p f d -> f d p').contiguous()

residualf, residualr = x, x

y = x.clone()

x = self.seq_layernormf(x)

x, y = self.convf(x) + residualf, self.convr(y) + residualr

residualf, residualr = x, y

x, y = self.patch_layernorm(x), self.patch_layernorm(y)

x, y = self.patch_ff(x) + residualf, self.patch_ff(y) + residualr

return x + y

At first glance it seems that we can just substitute this DoubleMixerBlock for a normal mixer block and proceed, but doing so for all models containing more than one mixer block leads to very fast loss minimization towards the origin (CEL $L(O(a, \theta), y)<0.1$ in less than half an epoch) suggesting that something went wrong. Closer examination of the figure above shows what happens: in that case, information from token $t_2$ reaches $t_0$ during the reverse convolution step, which is what we want. But then consider that in the next layer, information travels from hidden layers of $t_0 \to t_1$ and as the model predicts $t_2$ the hidden layer $t_1$, it learns a trivial mapping of that output. This phenomenon is perhaps easier to appreciated diagramatically, and can be shown as follows:

This problem is general to any token pair, and is not even specific to mixers as a bidirectional transformer experiences the same problem. Happily there is a simple solution: observe that two sequential convolutions are required for $t_{n+1}$ information to pass to $t_n$, which is why a model with only one mixer block will not rapidly minimize its loss function as a two or more blocked mixer will. Without loss of generality, one reverse and one forward convolution is required sequentially for this transfer. Therefore this problem may be avoided by placing all forward and reverse convolutions in parallel rather than in sequence, which can be implemented by having each block take both $x, y$ and return a tuple of both,

class DoubleMixerBlock(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor, y: torch.Tensor):

...

return x, y

where the linear combination only occurs after all blocks have been passed. The forward pass for the double-sided mixer becomes

class LanguageMixer(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None, **kwargs):

x = self.wte(x)

y = torch.clone(x)

for block in self.mixerblocks:

x, y = block(x, y)

output = self.lm_head(x + y) # combine after mixer blocks

# shift and CEL computation

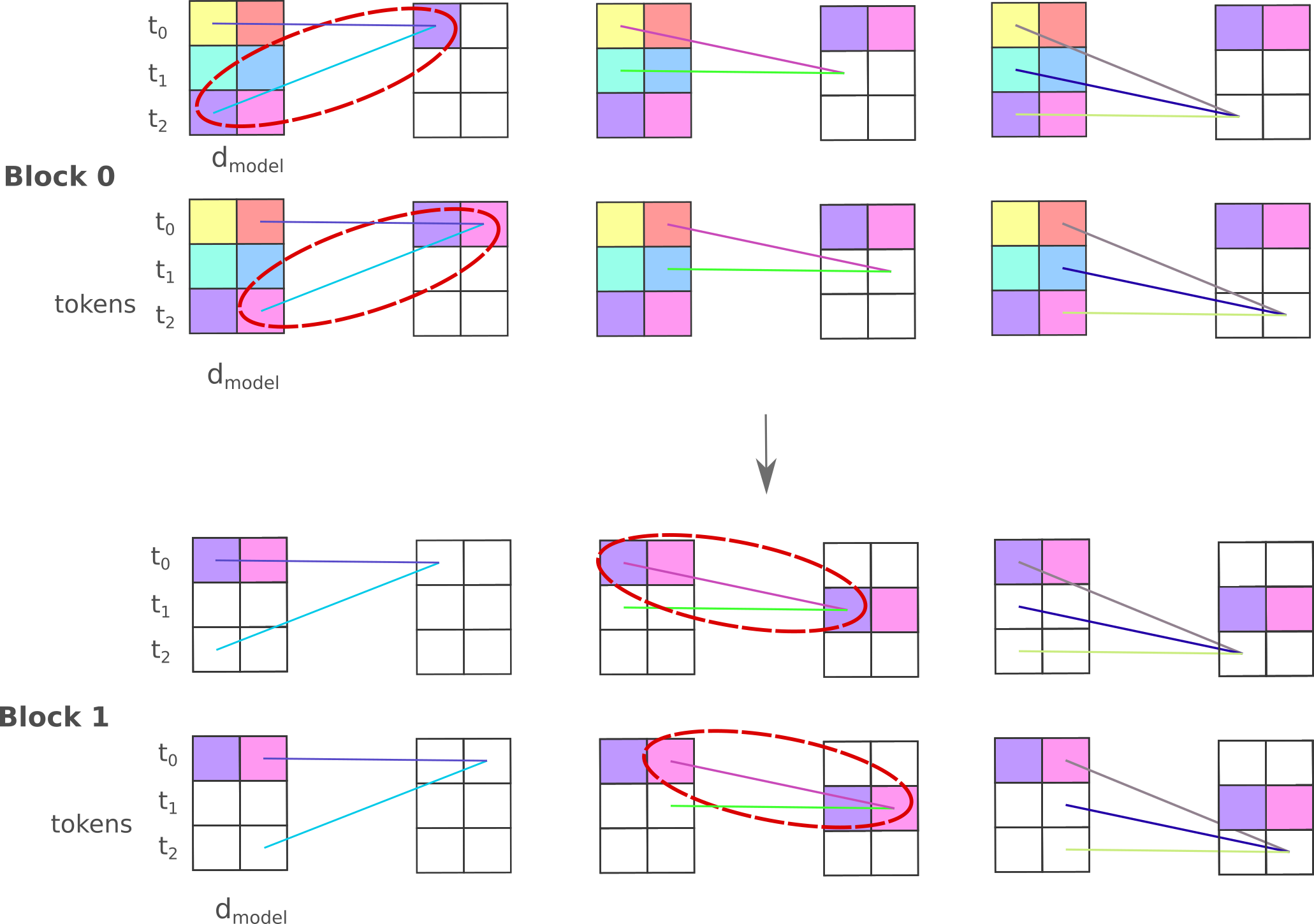

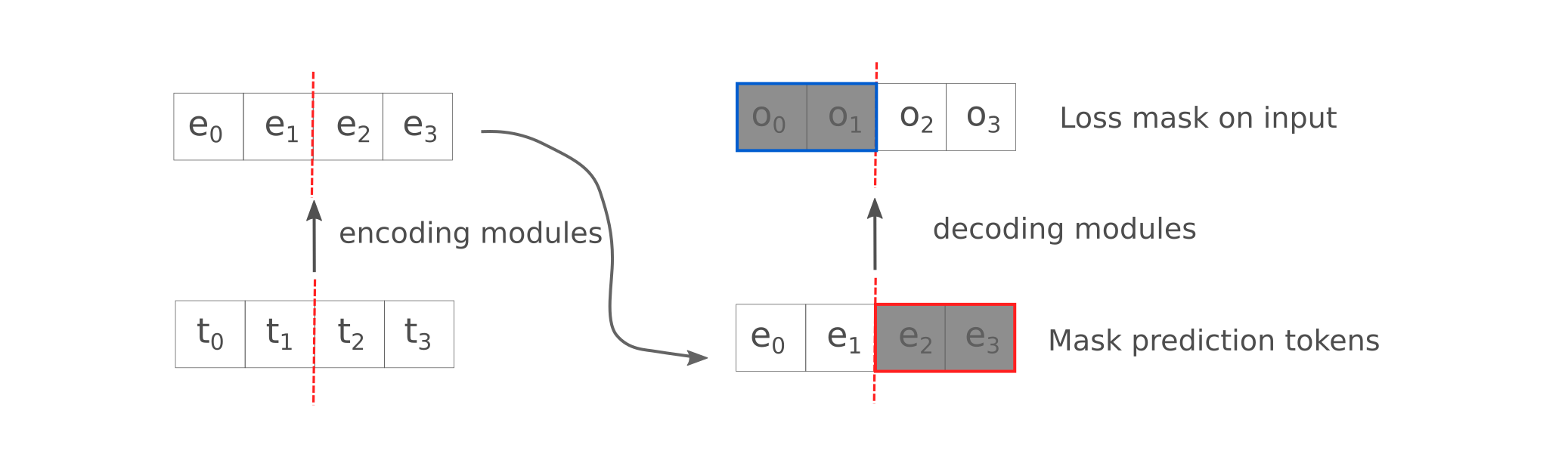

An analogous implementation may be made for a transformer, but this would require rewriting the causal langauge model mask on scaled dot-product attention layers to act in reverse with a changed $torch.triu$ diagonal. A simpler method is to keep the transformer blocks as they are normally implemented and instead reverse the sequence of $y$ such that the ‘reverse’ block sees tokens in reverse order via torch.flip(), maintaining a left-to-right causal mask. One can then undo the reversed y order in the token dimension and shift the forward and reverse last hidden layers such that their sequence indices align, add the result, and perform language model head linear transformation and loss calculation. Note that one does not need to truncate the labels as normally occurs, as the $t_0$ is predicted only in the reverse direction. A diagram showing how this works for a sequence of four tokens is given below.

An implementation of this is as follows:

class BidirectionalTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_vocab, dim, forward_model, reverse_model):

super().__init__()

...

self.forward_model = forward_model # transformer blocks only, no wte or lm_head

self.reverse_model = reverse_model # transformer blocks only, no wte or lm_head

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None, attention_mask=None):

x = input_ids

x = x.to(device).squeeze(1)

x = self.wte(x)

y = torch.flip(x.clone(), dims=[1]) # reversed in token dim

forward = self.forward_model(x)

reverse = self.reverse_model(y)

pad = torch.zeros(x.shape[0], 1, x.shape[2]).to(device)

reverse = torch.cat([torch.flip(reverse, dims=[1])[..., 1:, :], pad], dim=1) # right pad reverse

forward = torch.cat([pad, forward[..., :-1, :]], dim=1) # left pad forward

output = self.lm_head(forward + reverse)

logits = rearrange(output, 'b t e -> b e t')

loss = self.cel(logits, labels)

return loss, output

When we compare mixer versus transformer performance on bidirectional token prediction versus causal language modeling-style next token prediction on the fineweb-edu 10BT dataset, we see that the relative performance is nearly identical, suggesting that it is not language stochasticity but many-to-one mapping that give transformers a training efficiency advantage over masked mixers for token prediction.

Mathematics Causal Language Modeling Efficiency

The finding in the last section is that it is the many-to-one mapping rather than inherent language stochasticity that gives transformers an advantage in next token prediction relative to masked mixers. If the reader is not convinced that bidirectional language modeling is capable of telling us this, we can search for evidence for or against this idea elsewhere.

One good way of testing the hypothesis is to train these models on datasets that have much less language stochasticity than a natural language like English. What we want therefore is to observe training efficiencies on a dataset primarily composed of a formal language such as mathematics or a programming language. We chose the FineMath-4+ dataset available here to test this idea, as it closely mirrors the Fineweb-10BT dataset used elsewhere on this page in both size (9.6B tokens) and source (a refined version of the Common Crawl). We do not train a new tokenizer on this dataset, as examination of the entries therein reveals that is has a similar vocabular to the Fineweb-10BT dataset only with much more mathematical content. Most importantly, both datasets tend to include mathematical content in markdown format.

Recall that for the fineweb, we saw causal language model training to be more efficient for masked mixers of equivalent memory on device (during training) for smaller context windows ($n_{ctx}< 512$) but less efficient for larger context windows. We see a similar phenomena for the FineMath-4+ dataset, as shown below. Note that the $n_{ctx}=32$ mixer has 18 layers rather than the usual 16, this is to match the on-device memory requirements of the respective llama model.

Thus if we assume that a mathematicasl dataset such as FineMath-4+ contains less intrinsic noise than a general corpora dataset such as the fineweb, we find more evidence for the idea that it is not the intrinsic noise present in language but rather the nature of the mapping itself that differentiates transformer and masked mixer causal language model training efficiencies.

Multiple Token Prediction Training Efficiency

Recent work in the language modeling field has focused on extending the all-next-token prediction training (that still forms the basis of nearly all current models’ pretraining) using a variety of techniques such as output-only supervised finetuning, deep reinforcement learning via human feedback with algorithms like DPO and PPO, and most recently monte carlo tree search-based reinforcement learning for reasoning.

One particularly interesting extension is to train on multiple next tokens in one forward pass, which has lately been referred to as ‘multiple token prediction’ or ‘non-myopic pretraining’. As an example, Deepseek V3 has incorporated multiple token prediction into pretraining via specialized cross-attention modules. There are many other approaches to multiple next token prediction training, but the general idea is that during autoregressive inference one typically wants to predict not just one but many ‘next’ tokens in sequence, and including that information in a pretraining recipe might increase model inference fidelity.

Training a language model to predict multiple future tokens rather than simply one can be done in a number of ways, but perhaps the simplest method is to perform $n$ forward passes and collect the corresponding loss values for each of $n$ tokens predicted using the standard label shifting method shown previously. This can be implemented succintly for a transformer model as follows:

class MTPTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, model, n_tokens=2):

super().__init__()

self.model = model

self.n_tokens = n_tokens

self.cel = torch.nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

def forward(self, input_ids, labels=None, **kwargs):

x = input_ids

for i in range(self.n_tokens):

output = self.model.lm_head(self.model.model(x)[0])

output = rearrange(output, 'b t e -> b e t')

shift_logits = output[..., :-(1 + i)].contiguous()

shift_labels = labels[..., (1 + i):].contiguous()

if 'loss' in vars():

loss += self.cel(shift_logits, shift_labels)

else:

loss = self.cel(shift_logits, shift_labels)

x = torch.argmax(output, dim=-2)

return loss, output

We can initialize a two-token-ahead model for training via model = MTPTransformer(model, n_tokens=2) where the model is a LlamaForCausalLM object, but note that a masked mixer base model can be substituted as well. The results of two-token-ahead training are shown below for $n_{ctx}=512$, and show that as expected the efficiency gap between masked mixer and transformer has decreased relative to the one-token-ahead training (see above).

One Step Language Completion Efficiency

So far we have seen that masked mixers are better at tasks requiring approximately bijective functions such as autoencoding or retrieval, and worse at tasks requiring non-injective mappings such as causal language modeling (where many previous tokens are mapped to one next token). It could be wondered how efficiently each model learns a task that exhibits aspects of both non-injective and bijective mappings, say one-step text completion on a per-token basis. The hypothesis is that these models will be approximately equivalently efficient, assuming that this task requires a relatively even mix of bijective and non-bijective mappings because we map many previous tokens to individual next tokens as is the case for normal CLM, but at the same time we use a strict subset of previous tokens such that the map is more approximately one-to-one (ie lower context in the input).

To elaborate, the task is to generate all the completion tokens in a text segment in one step. Arbitrarily choosing text segments of length 512 such that the model recieves information from tokens (${t_0, t_1, .., t_{255}}$) and generates tokens ${t_{256}, t_{257}, … t_{511}}$, we want information from each of the first 256 tokens to be available for the subsequent 256 tokens during the forward pass. One way to do this would be to use the last hidden layer of token $t_{255}$ as an input to a decoder in a similar architecture to the autoencoders presented above, but this would require all input information to be present in that token and we have already seen that this sort of task is much better suited for masked mixers. Instead we want to provide information from all input tokens ${t_{0-255}}$ directly, while preventing the passage for information from the prediction tokens ${t_{256-511}}$.

Perhaps the most efficient way to accomplish this would be to change the causal language masking from lower triangular to block form (where the weights from all prediction tokens are masked, and weights from input to outputs are bidirectional). This would require substantial changes to the causal language masking implementation for transformers, however, but there is a much simpler method: retain causal langauge masking but mask the hidden layers of prediction tokens at a certain layer of the model. We use an encoder-decoder model in which the masking occurs half-way through the models layers (at layer 8 or a 16-layer model to be precise) paired with loss masking on the inputs. This can easily be applied to both masked mixers and llama-style transformers, and for clarity here is a depiction of this process:

As expected, there is nearly complete parity in training efficiency for the masked mixer and transformer when applied to this one-step completion paradigm for the Fineweb-10BT dataset. Note that both train relatively poorly: unsurprisingly, it turns out that attempting to predict many tokens at once in one step is much more difficult than predicting one token at a time.

Fineweb Retrieval via Direct Embeddings

We have seen that masked mixers are far more efficient learners than transformers for tasks requiring approximately bijective functions, whereas these models are somehwat less efficient for learning tasks requiring injective functions. In Part I it was observed that summary-story retrieval on TinyStories, a task requiring an approximately bijective mapping, is much easier for a masked mixer to learn than a transformer. Furthermore, embeddings from masked mixers provide far better trained retrieval model performance than embeddings from transformers, providing evidence for the idea that attention is somewhat unsuitable to the task of language retrieval.

So far we have observed that the findings on that dataset have translated very closely to the much larger and more difficult Fineweb. What about retrieval? Before guessing how mixers and transformers will fare on this task, we should examine how the process of retrieval differs for the fineweb versus tinystories. In many respects, it can be claimed that TinyStories retrieval is a quite difficult task for language models. This is mostly because many stories tend to have very similar structures, characters, and partly because the training task is very limited for the generative model (write small stories only). To illustrate the former point, taking a random sample of a 16 stories we find that the same characters tend to appear very frequently: ‘Ben’ and ‘Lily’ appear in six stories each, and ‘Anna’ appears in four.

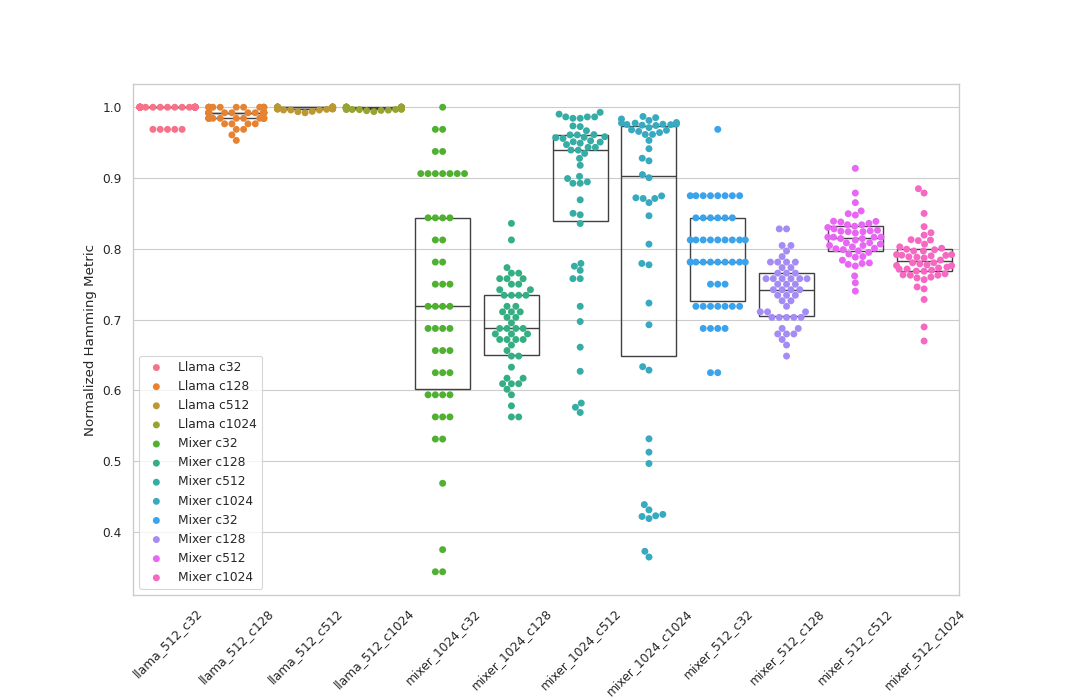

Thus we can expect retrieval model training to be ‘easier’ for summaries of Fineweb entries versus TinyStories. Additionally, there is much greater variety of content in the fineweb such that a given summary may be uniquely identified to its matching entry among a batch via only one or two keywords, such that one would expect for transformer embeddings to perhaps fare better than they did for TinyStories retrieval. We use the same retrieval training method as for TinyStories: a CLM-trained model is used to generate a second-to-last token’s last hidden layer activations for each summary and passage (here a 200k subset), and subsequently a non-masked mixer retrieval model is trained on these embeddings using standard cross-entropy loss (refer to this paper for more information on exactly how this training is achieved).

What we find when we observe performance of retrieval models on Fineweb summary and passage embeddings is that these guesses are more or less accurate: focusing on embeddings from $d_m=512$ CLM models with retrieval models trained on 200k of these samples, embeddings from masked mixers resulted in lower evaluation loss and faster optimization compared to embeddings from transformers. This is particularly apparent for retrieval models trained using large context windows (ie compare one summary sentence to many potential matching text excerpts): for $n_{ctx}=1024$ (one summary matched to one story among 1024 possibilities) we find that embeddings from a mixers gives a CEL of 1.2, whereas embeddings from the transformer result in the retrieval model failing to break symmetry even after a very large number of epochs of training, with a CEL of ~6.93 (see table below for full results).

It is interesting to consider what happens when we try a llama model with many more attention heads. The hypothesis is that these models would be better at retrieval, and we tested this with models trained using $n_h=32$ heads rather than four. We find that indeed embeddings from these models achieve somewhat lower retrieval evaluation loss than embeddings of transformers trained with $n_h=4$ for some context lengths, but are substantially worse than the embeddings from masked mixers once again.

| emb model | c32 | c128 | c256 | c512 | c1024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mixer | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 1.20 |

| llama h=4 | 0.55 | 1.24 | 1.76 | 1.84 | 6.93 |

| llama h=32 | 0.61 | 1.19 | 1.59 | 1.88 | 6.93 |

Before proceeding, it should be noted just how much faster the optimized retrieval model training method is than a standard infoNCE approach is. One way to look at this is to see how many total samples the retrieval model is able to train per second, irregardless of whether these are positive matches or negatives. By this approach we can train via batched InfoNCE 4 GPUs, each taking around 5 steps per second on batch sizes of 32 which gives us 640 samples per second. This is a staggeringly small amount compared to the throughput of the optimized retrieval training algorithm, which for each of 4 GPUs can use 128 embeddings per sample and 128 samples per GPU and 4 passes per second for a total of 262,144 samples per second. The sole benefit of using the standard infoNCE training algorithm is that forward passes during inference can be ‘cached’, meaning that one can obtain embeddings of corpora segments ahead of time and only needs to perform a forward pass on the query input followed by matrix multiplication.

Masked Mixers are better for InfoNCE-trained retrieval

The primary downside to the retrieval training method detailed in this work, is the test time compute requirement: we cannot save embeddings and simply perform matrix multiplication as a forward pass is required each time a retrieval is made. Experimentally another downside to this approach is that it tends to result in significant overfitting, as the cross-entropy loss minimization approaches the origin for the training dataset but not the test dataset (see the table above).

What this means in the bigger picture is that while the embedding retrieval training approach detailed above is effective even for small datasets and models, it fails to perform as well as state-of-the-art retrieval models pretrained with many GPUs and further trained for retrieval via minimization of some variant of noise-contrastive estimation. This training procedure involves

We can also observe which models are most suitable for training via modifying the CLM-trained base model itself for the purposes of retrieval. This is often achieved by minimizing a variant of noise-contrastive estimation, which is defined as follows: for a text excerpt $d^+$ with its matching summary $q^+$ with other non-matching text excerpts $n_i \in N$, we minimize

\[\Bbb L = - \log \; \frac{f(q^+, d^+)}{f(q^+, d^+) + \sum_{n_i \in N} (f(q^+, n_i))}\]where perhaps the most common metric $f()$ that is used for contrast is temperatured cosine similarity, in which case we have

\[f(a, b) = \mathrm{exp} \left( \frac{1}{\tau} \cos (O(a, \theta), O(b, \theta)) \right)\]where $O(a, \theta)$ is the model’s embedding of input $a$ with parameters $\theta$ and $\tau$ is a temperature parameter. Note that $\cos$ here signifies the trigonometric function itself also known as cosine similarity such that pairs of vectors pointing in similar directions have outputs closer to one, rather than cosine distance defined as $1-\cos(\phi)$. We modify this metric somewhat by removing $\tau$, after finding numerical instabilities for the small batches that can fit on one or a few GPUs.

It should be noted that this loss is similar to standard (unweighted) Cross-Entropy loss,

\[\Bbb l_n (x, y) = - \log \frac{\mathrm{exp} (x_{n, y_n})}{\sum_c \mathrm{exp} (x_{n, c})}\]There are two ways we can use multiple GPUs to train using this loss function: either we use Distributed Data Parallel and have one $q^+, d^+$ pair per GPU and all-gather gradients during each update, or else we have one $q^+, d^+$ pair across all inputs and compare across batches on different GPUs. The latter complicates implementation slightly because we cannot use a strict DDP training algorithm anymore, being that we need to communicate more than just gradients across GPUs. We therefore begin by using DDP, where each GPU has one $q^+, d^+$ pair.

The usual method for training retrieval models is to start with a model trained for a language task (usually causal language modeling) and proceed to further train for retrieval itself. InfoNCE is usually applied to train the model performing the embedding (which is the same as the model previously trained to predict all next tokens) such that the finished model generates embeddings that can be used for retrieval via a simple cosine similarity metric.

To train a model to perform retrieval using noise-constrastive estimation on CLM-trained model embeddings, we need to sample sequences of tokens from our dataset of queries and texts. As for our other experiments, we use a set of 200k summaries of Fineweb passages together with the matching passages themselves. A simple approach to this is to first tokenize each summary and text passage and then save these tokens as a single safetensors file, which may be read very quickly as this is a zero-copy file format. We access these tokens as follows:

path = "/path/to/safetensors"

tokens = {}

with safe_open(path, framework="pt", device=0) as f:

for k in f.keys():

tokens[k] = f.get_tensor(k)

# tokens is a dict with keys 'text' and 'summary' mapped to token sequences as tensors

The sampling procedure may be performed in a number of different ways, but the primary difficulty is that the transformers.Trainer class was not really designed for the purposes of matching entire sequences to each other such that sampling a batch using custom distributions becomes tricky when attempting. This difficulty may be obviated by creating a custom torch.utils.data.Dataset class that assembles the appropriate batch of inputs, such that the transformers.Trainer class specifies a batch size of 1 but each element is its own batch.

class RetrievalDataset(torch.utils.data.Dataset):

def __init__(self, text_tokens, summary_tokens, batch_size=64, replace=False):

self.summary_tokens = summary_tokens

self.text_tokens = text_tokens

self.context_length = len(summary_tokens[0])

self.prob_weights = torch.ones(len(summary_tokens))

self.allocated_input = torch.zeros((batch_size, self.context_length))

self.replace = replace

self.batch_size = batch_size

def __getitem__(self, idx):

input = torch.zeros((self.batch_size, self.context_length)) # b t shape

input[0] = self.summary_tokens[idx]

self.prob_weights[idx] = 0

indices = torch.multinomial(self.prob_weights, self.batch_size-1, replacement=self.replace)

self.prob_weights[idx] = 1

input[1:] = self.text_tokens[indices]

target_index = random.randint(1, self.batch_size-1) # random index to put target embedding

matching_target = self.text_tokens[idx] # target the query matches

#print (matching_target, self.summary_tokens[idx])

input[target_index] = matching_target

labels = torch.tensor(target_index, dtype=torch.long)

retrieval_dict = {'input_ids': input.to(torch.long), 'matching_index': labels} # results in p b t shape upon load

return retrieval_dict

def __len__(self):

return len(self.summary_tokens)

Noise-contrastive estimation loss itself implemented in a batchwise mannar as follows:

def infoNCEloss(output, matching_index=None, embedding_index=-2):

"""

Implements Noise-Contrastive Loss. Assumes that there is one positive pair per batch and all

the rest are negative samples.

"""

summary_embedding = output[0, embedding_index, :].unsqueeze(0) # b t e shape

match_embedding = output[matching_index, embedding_index, :]

nonmatch_embeddings = torch.cat((output[1:matching_index, embedding_index, :], output[matching_index+1:, embedding_index, :]), dim=0)

cosine_sim = torch.nn.CosineSimilarity(dim=1)

temp = 0.02

codists = torch.exp((1/temp)*cosine_sim(summary_embedding, match_embedding))

nondists = torch.sum(torch.exp((1/temp)*cosine_sim(summary_embedding, nonmatch_embeddings)))

loss = -torch.sum(torch.log(codists / (codists + nondists)))

return loss

This is a fairly straightforward but non-optimized implementation: we use torch.nn.CosineSimilarity to compute the cosine similarity first between the embedding of the summary and the embedding of the matching text, and then computes the sum of the cosine similarites between embeddings of the summary and the non-matching text segments before computing the temperatureless noise-contrastive loss. The embedding_index is usually set to the last token in the literature (ie -1), but we test both last and second-to-last embeddings as masked mixers are not trained on the last token.

With our loss and data access methods implemented, we apply a masked mixer that was CLM-pretrained on the Fineweb-10BT by loading the model and then modifying its forward call to unbatch our prebatched input, pass the resulting inputs to the mixer blocks, and then obtain the noise-contrastive estimation loss using the above function.

class RetrievalMixer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_vocab, dim, depth, prebatched_input=True):

super().__init__()

self.prebatched_input = prebatched_input

...

def forward(self, input_ids, matching_index, **kwargs):

x = input_ids

if self.prebatched_input:

x = x.squeeze(0) # p b t -> b t

x = x.to(device)

x = self.wte(x)

for i, block in enumerate(self.mixerblocks):

x = block(x)

output = x

loss = infoNCEloss(x, matching_index=matching_index)

return loss, output

We can perform an analogous modification to a CLM-pretrained Llama style transformer by simply passing the unbatched input through the base model.model which omits the language modeling head before passing the output (hidden layer activations) to the infoNCE loss function.

class RetrievalTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, model, prebatched=True):

super().__init__()

self.model = model.model # no lm head

self.prebatched = prebatched

def forward(self, input_ids, matching_index, *kwargs):

# LlamaModel forward pass

if self.prebatched:

input_ids = input_ids.squeeze(0) # p b t -> b t

model_output = self.model(input_ids)[0]

loss = infoNCEloss(model_output, matching_index=matching_index)

return loss, model_output

For both masked mixer and transformer, we pretrain on models that are exposed to left-padded inputs in order to be able to take the last token’s hidden layer for infoNCE loss. A modification to our loss function allows one to pretrain on right-padded inputs and then extract the last non-pad token embedding rather than the last (or second-to-last) token embedding and proceed with NCE calculation.

As for the direct embedding training method detailed previously, InfoNCE results in very fast convergence in the training set for summary-to-passage retrieval of Fineweb text excerpts. This is somewhat surprising as it is common in the literature to see batch sizes far larger than the ones we use here, for example the Mistral e5 paper describing the retrieval training process as using batches of size 2048 requiring 32 V100s (presumably 32GB vRAM each) for LoRA training of the 7b parameter Mistral model.

The two major advantages of InfoNCE over direct embedding model training are as follows: firstly training to generate embeddings that can be compared by a simple operation like cosine distance allows one to ‘cache’ many embeddings by performing batched forward passes of the target text segments before inference, before looking up the target embeddings when one performs the forward pass on the query (followed by cosine distance computation). The second becomes apparent after training many retrieval models: direct embedding training tends to overfit the retrieval training dataset, whereas InfoNCE typically does not as we train on only a single epoch rather than dozens.

As our approximately state-of-the-art retrieval model achieves near-100% accuracy on fineweb sentence summary-to-passage retrieval (at 32 and 64 samples per batch) we introduce a new retrieval dataset that is much more challenging: given selections of Finemath text, a Llama 3.1 (8b) model is instructed to give a few-word summary for each. This is a more challenging retrieval task for three reasons: firstly because the subject matter is relatively invariant (every passage is math-focused) compared to the broader fineweb dataset, secondly because the queries contain fewer words and thus fewer uniquely identifying information, and finally because the generative model used was found to be rather incapable of ‘understanding’ much of the mathematical content of each passage and tended to give summaries that were difficult to match with a quick read.

This difficulty is borne out when we compare the accuracy achieved by the top-1 accuracy achieved by the near-SOTA e5 Mistral Instruct (7b) for samples of 32 passages per forward pass of the Fineweb retrieval (100%) to that achieved for the same number of passages of the new Finemath derived retrieval dataset (81.3%). We consider the latter dataset to be more realistic for a retrieval task in the real world, where search terms are typically not well-formed entire sentences for each query but rather a few keywords in uncertain order, for datasets that are more homogenous than the Fineweb. For these reasons we focus on the Finemath-derived dataset and test the ability of a Llama-style transformer and a masked mixer to accurately retrieve passages given queries.

The training method proceeds as follows: first the mixer or Llama model is initialized with random weights and then pretrained on the Finemath 4+ dataset, with context windows of length 512. Note that the mixer has essentially fixed positional information, so we train that model using left padding whereas the transformer does not and can be trained with either left or right padding. Pretraining occurs for 200k steps, requiring approximately 20 hours to complete via 4x V100 GPUs. Once pretraining is completed, we then continue training on the first 180k retrieval samples via batched infoNCE loss, holding out the last 20k as our test dataset, using batches of size 32 (ie matching one query to 31 potential target text segments with one positive per group) and left-padded inputs. Typically most target inputs do not receive pad tokens, but the query is mostly pad tokens due to its brevity. This retrieval training proceeds for one epoch (45k steps on 4x V100s) and requires around two and a half hours. As masked mixers with identical $d_m$ to transformers are much more memory- and compute-efficient to train for these context windows, we increase the number of masked mixer layers to $32$ rather than the usual $16$.

We then measure the top-1 accuracy of the hold-out test dataset, where neither the query nor target sequences were exposed during the infoNCE training procedure. The results for the models pretrained on the Finemath 4+ dataset followed by InfoNCE training on the retrieval dataset (train split), all models have 16 layers unless otherwise denoted. Recall that the $d_m=512, n_l=32$ and the $d_m=1024, n_l=16$ masked mixers were trained using approximately the same compute and device memory as the $d_m=512, n_l=16$ Llama-style transformer, which is why these models are included for comparison. It should also be noted we applied causal language modeling training to transformers on both right-padded and left-padded datasets, and no difference was found in top-1 accuracy after InfoNCE training. All models (except e5 Mistral Instruct) were trained using a 200k-sample sized retrieval datset unless otherwise noted. e5 Mistral Instruct was implemented with 4-bit quantization via the very helpful bitsandbytes library, which was confirmed to result in equivalent accuracy to the 16-bit version of this model.

| Model | Top-1 Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Transformer, $d_m=512$ | 66.2 |

| Masked Mixer, $d_m=512$ | 82.1 |

| Masked Mixer, $d_m=512, n_l=32$ | 84.6 |

| Masked Mixer, $d_m=1024$ | 86.0 |

| Transformer, $d_m=512$, n=400k | 95.0 |

| e5 Mistral Instruct, $d_m=4096$ | 95.1 |

| Masked Mixer, $d_m=1024$, n=400k | 98.2 |

The first conclusion we can draw here is that the masked mixer is once again a substantially more accurate retrieval model compared with the transformer assuming the two have undergone identical training (in this case, pretraining on one dataset with fixed number of steps with model architectures variable to keep vRAM constant, followed by InfoNCE retrieval training using equivalent steps). This suggests that not only is a CLM-trained mixer’s embedding more suitable to retrieval (as we saw in the last section), but that the masked mixer itself is more suitable to retrieval training via a contrastive loss method such as InfoNCE.

This is particularly notable because the transformer model in the above table reaches lower train/eval loss (CEL values of 1.36, 1.39) than either the $d_m=512, n_l=32$ mixer (CELs of 1.62 and 1.65, respectively) or the $d_m=1024, n_l=16$ model (CELs of 1.48, 1.53). It has been shown in the literature that models with better representations of their inputs w.r.t. causal langauge modeling (ie next token prediction) usually also exhibit better retrieval properties, so the finding that masked mixers substantially outperform the transformer model even without matching the CLM loss suggests that the mixers would outperform the transformer by an even wider margin if pretraining were continued until these models matched the CEL values of the transformer.

What is perhaps more remarkable here is that the masked mixer (with a bit more retrieval training data) also substantially outperforms a transformer model that approximates the current state of the art in the retrieval field, or at least the state-of-the-art when this project was started (early 2024). To gain an appreciation for what this means, it is helpful to note the scale of the computational resources with which each model is trained. It is unknown exactly how many GPUs and for how long the Mistral 7b model was pretrained for causal language modeling, or even whether this model was indeed trained from scratch without weight transfer (ie from Llama 1), but interpolating this model’s performance with others for which data is available such as Llama 2 (8b) which required 184320 A100 GPU-hours and Llama 3.1 (8b) which required 1.46M H100 hours suggests that the 7b Mistral model would require at least 500k A100 GPU-hours for pretraining, as a rough ballpark figure. Assuming an equivalence of 1.5 * V100 = A100 (which is empirically a fairly accurate value for for 16/32 bit mixed precision training) we get 750k V100 GPU-hours, which is approximately 10,000x the amount of compute that the transformer and masked mixer was pretrained with (80 GPU-hours). The e5 Mistral Instruct model was then retrieval-trained with 32 V100s (presumably 32GB each due to the memory requirements of the specified batch) over days, which is between 100x and 1,000x the compute we used here for the retrieval training process.

These numbers are purely illustrative, as a thorough measurement of just how much more efficient masked mixers are than transformers for retrieval would require an in-depth scaling study. We leave this to future work, and only comment on the ability to train a masked mixer to surpass a near-SOTA retrieval model’s accuracy for a task both are trained for using a miniscule fraction of the compute the latter required.

It could be argued that this comparison between the e5 Mistral instruct and the mixer models trained here is unfair, but close examination reveals that this claim could be made on either side. On the one hand, mixers and the llama style transformer were pretrained on the Finemath dataset whereas the e5 Mistral instruct model was probably not trained on this mix of word problems (although it was almost certainly trained on a fair amount of mathematical data). CLM pretraining on I.I.D. data to the retrieval targets (or even the retrieval targets themselves) does indeed increase retrieval accuracy, as can be seen for a $d_m=512, n_l=16$ masked mixer’s Finemath retrieval scores when two different pretraining datasets are applied:

| Pretraining Dataset | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

Fineweb-10BT, 1 epoch |

69.0 |

Fineweb-10BT autoencoder, 1 epoch |

70.7 |

Fineweb-10BT, 2 epochs |

71.3 |

Finemath 4+, 1 epoch |

81.8 |

A counterargument for this is that the Fineweb-10BT dataset is presumably much smaller (by a factor of perhaps 1,000x) than the dataset used to train Mistral 7b, and would contain far less mathematical text in total. This means that the dataset used to train Mistral 7b likely contained as much if not more mathematical text than the Finemath 4+ dataset, meaning that a comparison with the Fineweb-10BT is not particularly germane. Another argument on the side of the masked mixer is that the retrieval training methods are more or less completely non-optimized: for example if we extend the InfoNCE training to 2 epochs instead of one, we find that the Fineweb-10BT-pretrained mixer’s test accuracy increases slightly to 71.3%. A much larger performance gain is obtained by simply training on much more retrieval data (see the table before the last for evidence), and this likely accounts for a portion of the performance gain of the small mixer and transformer compared to e5 Mistral.

From the data presented above, it is evident that the masked mixer is much more effective for retrieval when trained on the 200k-sized synthetic retrieval dataset (180k training and 20k evaluation samples to be precise). It may be wondered whether a transformer trained on the larger 400k-size retrieval datset is also capable of outperforming the e5 Mistral model on this datset’s evaluation samples, as would be the case if most of the benefit to

| Model | $n=32$ | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 | 8192 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 95.0 | 92.3 | 88.9 | 84.5 | 79.1 | 72.6 | 65.7 | 57.6 | 50.4 |

| e5 Mistral | 95.1 | 93.3 | 90.9 | 88.5 | 85.6 | 82.2 | 78.4 | 73.5 | 68.8 |

| Masked Mixer | 98.2 | 97.2 | 95.8 | 93.4 | 90.2 | 86.5 | 81.7 | 76.6 | 70.6 |

The substantial increase in $n=32$ sample size retrieval accuracy for the transformer with the increase in dataset size (from 180k to 380k samples) makes one wonder whether this model would become more accurate than the e5 Mistral model if it were to be trained on many more samples, even if it never matches the accuracy of the masked mixer trained on the same data. We can address this question by doubleing the InfoNCE synthetic retrieval training dataset size (400k to 800k total samples, or 380k to 780k training samples) and training each model. The accuracy on the hold-out test set for transformer and masked mixer are below, with e5 Mistral included for reference.

| Model | $n=32$ | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 | 8192 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 95.8 | 93.3 | 90.2 | 86.0 | 80.8 | 74.4 | 67.6 | 60.5 | 52.6 |

| e5 Mistral | 95.1 | 93.3 | 90.9 | 88.5 | 85.6 | 82.2 | 78.4 | 73.5 | 68.8 |

| Masked Mixer | 98.6 | 97.8 | 96.5 | 94.5 | 91.7 | 88.5 | 83.8 | 79.0 | 73.9 |

We can draw a couple of noteworthy of observations from this experiments. Firstly these results suggest that it would require a dataset of gargauntuam proportions for the transformer to match the masked mixer’s retrieval accuracy: this can be shown by making an assumption where perform a single linear extrapolation to esimate that the next dataset doubling will add $0.153$ to the accuracy value (as the first two doublings add accuracy differences of 31.6 and 2.2), and then ignore the exponential decay of this increase further and assume that all doublings will yield this value. Note that this assumption almost certainly overestimates the accuracy at a given number of samples for this model. Even with this model, we require a dataset that is

\[2^\frac{70.6-50.4}{0.153} \approx 2^{132} > 5 * 10^{39}\]times as large as that for a masked mixer for the transformer to match the masked mixer’s $s=8192$ accuracy at 400k training samples as an upper bound, which is clearly an infeasibly large number. Secondly, The addition of more data is more beneficial to the masked mixer than transformer, with the former model increasing its 8192-size retrieval accuracy by a factor of 1.5x relative to the increase in the transformer upon dataset size doubling.

With this data, we can begin to answer the question of just how much more effective masked mixers are for retrieval compared to transformers. From the compute quantity estimation for e5 Mistral versus our masked mixer for this specific task, it could be claimed that the masked mixer 50,000x more compute efficient. From the dataset scaling results above, it could be claimed that the masked mixer is on the order of a trillion times more efficient with respect to the amount of data required for high large-context accuracy. These values are both very imprecise by nature but do give some appreciation for just how effective masked mixers are for retrieval compared to transformers.

Autoencoders may also be used for effective retrieval

Below are the results of the mixer and transformer autoencoder applied to the retrieval datset of size $s=400k$.

| Model | $n=32$ | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 | 8192 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 94.4 | 92.0 | 88.4 | 84.3 | 79.1 | 73.1 | 67.0 | 60.6 | 53.3 |

| Masked Mixer | 97.1 | 95.4 | 93.1 | 90.0 | 86.3 | 82.1 | 76.7 | 70.7 | 64.5 |

Representation Accuracy