Parallelizing the Three Body Problem across many GPUs

Single CPU threaded parallelization

In Part II we explored a number of different optimization strategies to make integrating a three body problem trajectory faster. The most effective of these (linear multistep methods) are unfortunately not sufficiently numerically stable for very high-resolution divergence plots at small scale, although compute optimizations when stacked together yielded a significant 4x decrease in runtime to Newton’s method.

Perhaps the easiest way to further decrease the runtime of our three body kernel is to simply choose a device that is best suited for the type of computation required. In particular, the Nvidia RTX 3060 (like virtually all gaming GPUs) has poor support for the double precision computation that is necessary for high-resolution three body problem integration, so switching to a datacenter GPU such as the P100, V100, A100 etc. with more 64-bit cores will yield substantial speedups. Indeed, this is exactly what we find when a V100 GPU is used instead of our 3060: a 9x decrease in runtime compared to the 3060. This is effectively stackable on top of the

Another way to speed up the computational process is to use more than one GPU. This is a common approach in the field of deep learning, where large models are trained on thousands of GPUs simultaneously. Sophisticated algorithms are required for efficient use of resources during deep learning training, but the three body problem simulation is happily much simpler with respect to GPU memory movement: we only need to move memory onto the GPU at the start of the computation, and move it back to the CPU at the end.

This is somewhat easier said than done, however. A naive approach would be to split each original array into however many parts as we have GPUs and then run our kernel on each GPU, and then combine the parts together. This approach has a few problems, however: firstly it would require a substantial re-write of our codebase, secondly copying memory from CUDA device to host must require pre-allocated space which is difficult in this scenario, and more importantly because the GPUs will not execute their kernels in parallel but in sequence. Because of this, we need to modify our approach. The goal will be to do so without modifying the kernel itself, as it is highly optimized already.

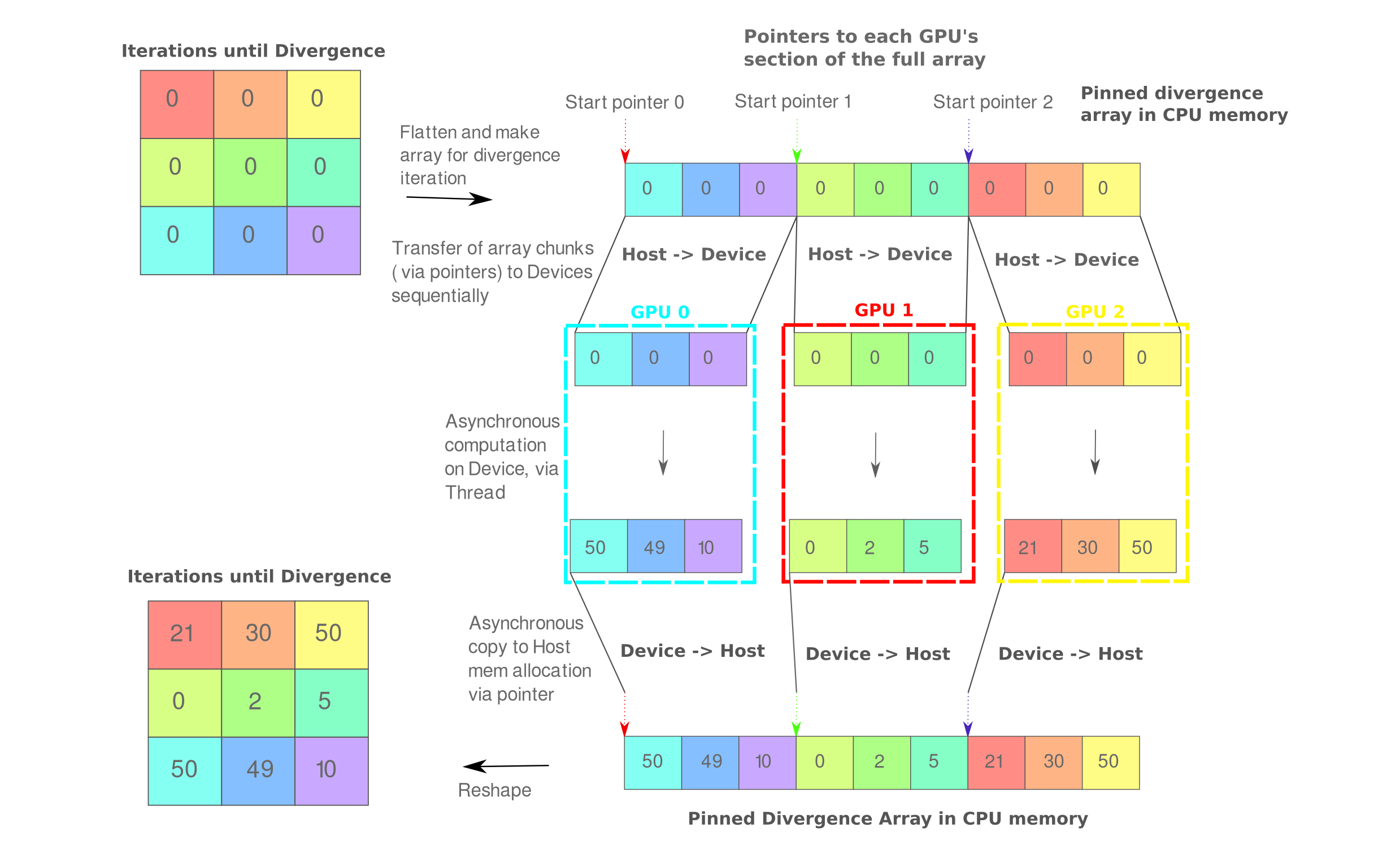

Perhaps the most straightforward way to do this is to work in the single thread, multiple data paradigm. The essentials of this approach applied to one array are shown below:

Briefly, we first allocate CPU memory for each array in question (shown is the divergence iteration number array but also required are all positions, velocities etc.), find which index corresponds to an even split of this flattened array and make pointers to those positions, allocate GPU memory for each section and copy from CPU, asynchronously run the computations on the GPUs (such that the slowest device determines the speed), and asynchronously copy back to CPU memory. This is all performed by one thread, and happily this approach requires no change to the divergence() kernel itself.

The first step (allocating CPU memory) requires a change in our driver code, however: asynchronous copy to and most importantly from the GPU requires paged-locked memory, rather than the pageable memory get when calling malloc(). Happily we can allocate and page-lock memory using the cudaHostAlloc call as follows: for our times divergence array of ints, we allocate using the address of our times pointer with the correct size and allocation properties.

int *times,

cudaHostAlloc((void**)×, N*sizeof(int), cudaHostAllocWriteCombined | cudaHostAllocMapped);

This replaces our malloc() used in the previous section. We repeat this for all arrays (x, y, z, velocity etc.) and can then initialize the arrays with values exactly as before, ie

int resolution = sqrt(N);

double range = 40;

double step_size = range / resolution;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

times[i] = 0;

}

After allocation and initialization, we can find the number of GPUs we have to work with automatically. This can be done using the cudaGetDeviceCount function which expects a pointer to an integer, and assigns that integer the proper value via the pointer.

int n_gpus;

cudaGetDeviceCount(&n_gpus);

Now that our arrays are allocated and initialized and we know the number of gpus in our system, we can proceed with distributing the arrays among the GPUs present. This is done by supplying cudaSetDevice() with an integer corresponding to the GPU number (0, 1, 2, etc.). As we are splitting each array into $n_gpus$ parts, it is helpful to assign variables to the number of array elements per GPU (block_n) as well as the starting and ending pointer positions for each block.

// launch GPUs using one thread

for (int i=0; i<n_gpus; i++){

std::cout << "GPU number " << i << " initialized" << "\n";

// assumes that n_gpus divides N with no remainder, which is safe as N is a large square.

int start_idx = (N/n_gpus)*i;

int end_idx = start_idx + N/n_gpus;

int block_n = N/n_gpus;

cudaSetDevice(i);

Now we can proceed as before, using memory allocations such as cudaMalloc(&d_p1_x, block_n*sizeof(double)); for each necessary sub-array of size block_n. After doing this we can copy just the GPU’s block of memory to each allocated space (we don’t actually need to specify an asynchronous memory copy)

cudaMemcpy(d_p1_x, p1_x+start_idx, block_n*sizeof(double), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

and call the kernel divergence<<<(block_n+127)/128, 128>>>. After the kernel is called we need to asynchronously copy memory back to the CPU as follows:

cudaMemcpyAsync(p1_x+start_idx, d_p1_x, block_n*sizeof(double), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

which allows the loop to continue without waiting for each GPU to finish its computation and send data back to the CPU memory.

There are two final ingredients that we need to finish adapting this code for use with multiple GPUs. Firstly we need a synchronization step to prevent the process from completing prematurely. This can be done by adding cudaDeviceSynchronize(); after the loop over n_gpus, which prevents further code from executing until the cuda devices on the current thread (all GPUs in this case) have completed their computation. Lastly we need to de-allocate our pinned memory: simply calling free() on the cudaHostAlloc() arrays leads to a segfault, one must instead use the proper cuda host deallocation. Instead we need to explicitly free the pinned memory via the cuda function cudaFreeHost(var).

With that, we have a multi-gpu kernel that scales to any number of GPUs. The exact amount of time this would save any given computational procedure depends on a number of variables, but one can expect to find near-linear speedups for clusters with identical GPUs (meaning that for $n$ GPUs the expected completion time is $t/n$ where $t$ is the time to completion for a single GPU). This can be shown in practice, where a cluster with one V100 GPU completes 50k iterations of a 1000x1000 starting grid of the three body problem in 73.9 seconds, whereas four V100s complete the same in 18.8s which corresponds to a speedup of 3.93x, which is very close to the expected value of 4x.

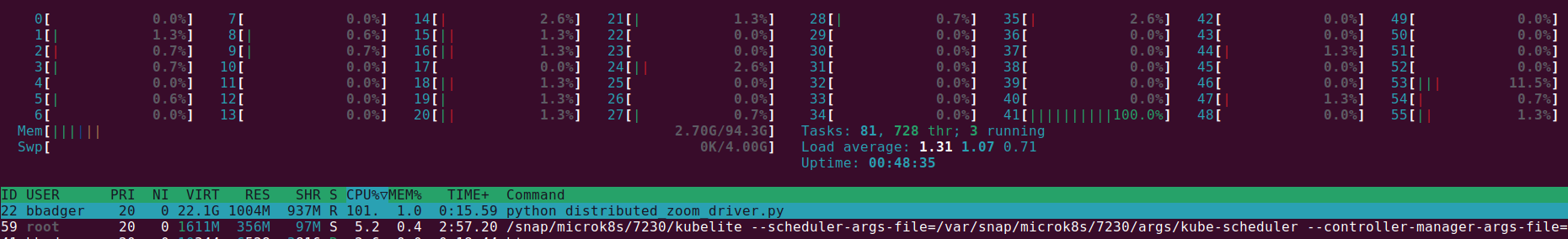

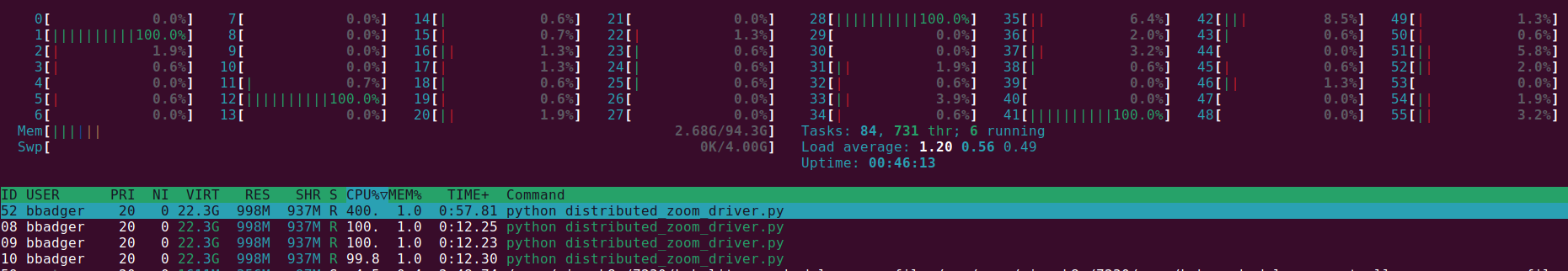

We can see this approach in action by observing the CPU and GPU utilizations while the simulation is underway. For a 56-core server CPU, we see that only one core is highly utilized: this is the thread that is running our four GPUs.

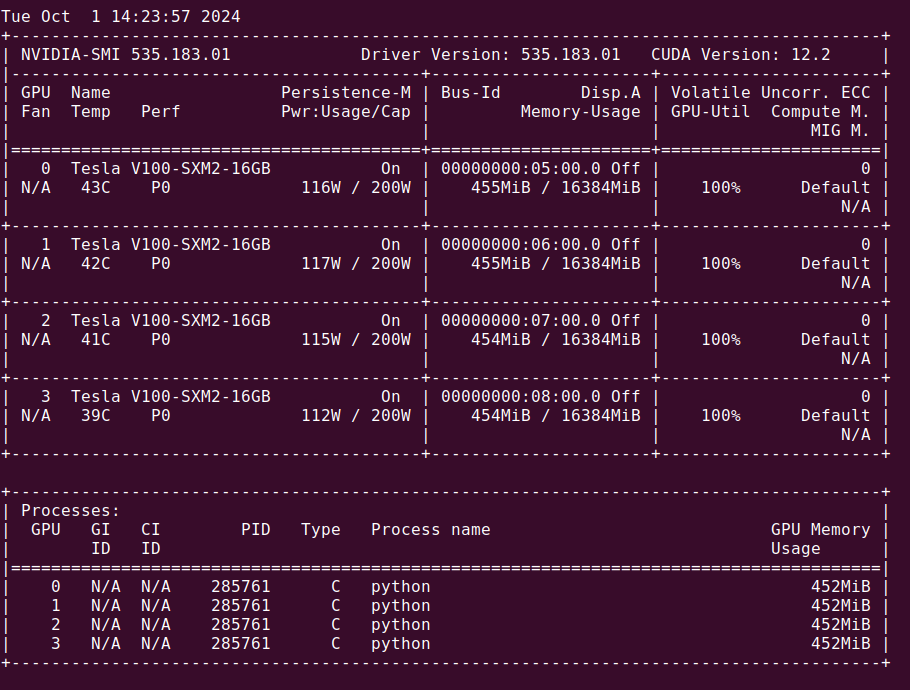

And the GPUs may be checked via nvidia-smi, which shows us that indeed all four GPUs for this server are occupied with the simulation

This is not quite the end of our efforts, however: we have thus far avoided performing cuda memory de-allocation, instead relying on automatic deallocation to occur after the kernel processes are completed (and the CPU process is terminated). But if we want to call this kernel repeatedly, say in a loop in order to obtain a zoom video, this approach is not quite complete and gives memory segmentation faults in a hardware implementation-specific manner. Why this is the case and how one can change the approach will be detailed in the last section on this page, as it is closely related to a problem we will find for multi-threading in the next section.

Multithreaded Parallelization

Suppose that one wanted to squeeze a little more performance out of a compute node containing more than one GPU. How would one go about making all GPUs perform as closely as possible to what can be achieved with only one device?

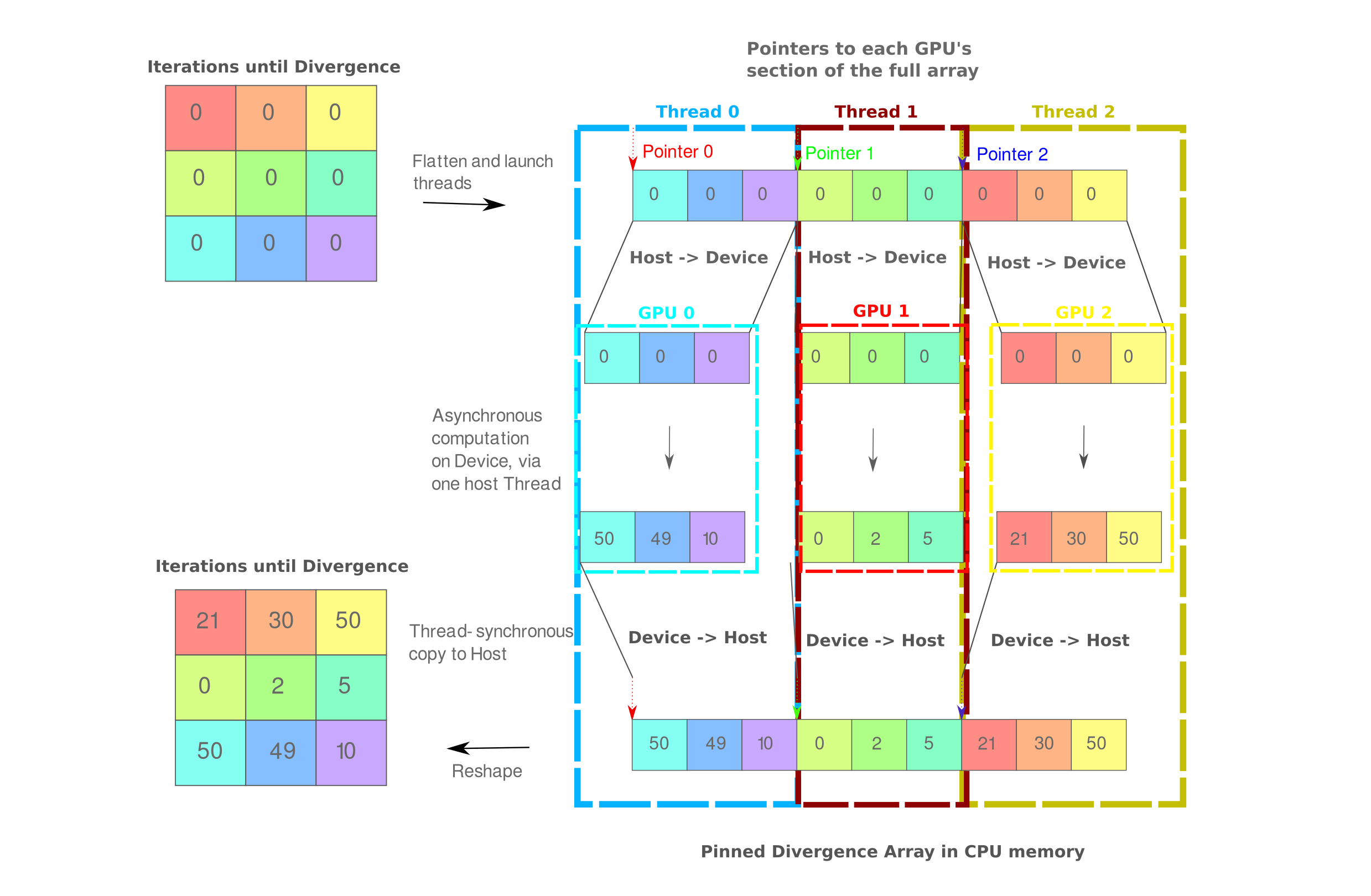

One way to do this is conceptually straightforward: each GPU is assigned a single CPU thread. This should prevent a situation from occuring where one device waits for instructions from the CPU while it is sending other instructions to a different device. All we need is for the number of CPU threads to meet or exceed the number of GPU devices per node, which is practically guaranteed on modern hardware (typically one has over 10 CPU threads per GPU).

It should be noted that this approach would only be expected to realize the smallest increases in performance for the three body simulation because this kernel is already highly optimized to remove as much communication from the CPU to GPU. One should not see any instances of a device waiting for a thread during kernel execution because no data and very few instructions are sent from CPU to GPU during kernel execution. This is apparent in the near-linear speedup observed in the last section. Nonetheless, as something of an exercise it is interesting to implement a multi-threaded multi-GPU kernel.

In practice multithreading a CUDA is more difficult because threading is usually implementation-specific, and combining multithreading with GPU acceleration is somewhat finnicky for a heave kernel like the one we have. The C libraries standard for multithreading (OpenMP, HPX, etc) were developed long before GPUs were capable of general purpose compute, and are by no means always compatible with CUDA. We will develop a multithreading approach with OpenMP that will illustrate some of the difficulties in doing so here.

Multithreading is in some sense a simple task: we have one thread (the one that begins program execution) initialize other threads to complete sub-tasks of a certain problem, and then either combine the threads or else combine the output in some way. The difficulty of doing this is that CPU threads are heavy (initializing a new thread is costly) and memory access must be made in a way to prevent race conditions where two threads read and write to the same data in memory in an unordered fashion. Happily much of this difficulty is abstracted away when one uses a library like OpenMP, although these are slightly leaky abstractions when it comes to CUDA.

We begin as before: arrays are allocated in pinned memory,

cudaHostAlloc((void**)&x, N*sizeof(float), cudaHostAllocWriteCombined | cudaHostAllocMapped);

and then initialized as before, and likewise the number of GPUs is found. To make things more clear, it is best practice to use explicit data streams when sending data to multiple devices, rather than relying on default streams. Here we make an array of n_gpus streams.

cudaStream_t streams[n_gpus];

and now we can use OpenMP to initialize more threads! OpenMP is one of the most widely-used multithreading libraries, and is used by Pytorch under the hood for distributed deep learning training algorithms such as Distributed Data Parallelism. It is typical to use one thread per GPU for those applications as well.

This can be done a few different ways: one would be to wrap the for loop in the last section (looping over devices) with the preprocessor directive #pragma omp parallel for, but this turns out to lead to difficult-to-debug problems with cuda memory access when more than two devices are used. It turns out to be more robust to proceed as follows: first we initialize one thread per device, we get the thread’s integer number and assign the thread to the corresponding GPU device, and then we create a stream between that thread and the device.

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(n_gpus)

{

int d=omp_get_thread_num();

cudaSetDevice(omp_get_thread_num());

cudaStreamCreate(&streams[d]);

After doing so, we can allocate memory on the device for the portion of each array that device will compute. One must use cudaMemcpyAsync for both host->device as well as device-> host communication, and for clarity we also specify the stream associated with that device and thread in both memory copies and kernel call. Finally we synchronize each thread rather than the first driver thread.

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(n_gpus)

{

...

// H->D

cudaMalloc(&d_x, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float));

cudaMemcpyAsync(d_x, x+start_idx, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, streams[device]);

// kernel call

divergence<<<(block_n+255)/256, 256, 0, streams[d]>>>(...)

// D->H

cudaMemcpyAsync(x+start_idx, d_x, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, streams[device]);

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

}

The following figure gives a simplified view of this process:

The cuda kernel and driver code can be compiled using the -fopenmp flag for linux machines as follows:

badger@servbadge:~/Desktop/threebody$ nvcc -Xcompiler -fopenmp -o mdiv multi_divergence.cu

After doing so we find something interesting: parallelizing via this kernel is successful in a hardware implementation-specific manner. For a desktop with two GPUs there is no problem, but on a 4x V100 node with three or four GPUs available we find memory access errors that result from the CPU threads attempting to load and modify identical memory blocks. Close inspection reveals that this is due to the CPU (actually two CPUs for that node) attempting to access one identical memory location for each thread, which may be found by observing the string associated with the thrown cudaError_t,

cudaError_t err = cudaGetLastError();

if (err != cudaSuccess) std::cout << "CUDA error: " << cudaGetErrorString(err) << std::endl;

Why does this happen? Consider what occurs when we call the following

cudaMalloc(&d_x, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float));

cudaMemcpyAsync(d_x, x+start_idx, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, streams[device]);

with four different threads. Each thread is attempting to allocate memory on its ‘own’ device, but the address must be fetched and is identical as the variable double *d_x was only initialized once. Thus if we print the address of d_x for each thread we have one identical integer, which for me was the following address:

std::cout << &d_x; // 0x7ffedb04f2e8

Now for newer hardware implementations this does not lead to immediate problems because CPU threads are scheduled such that they do not experience read conflicts with d_x. But older hardware is not so lucky, and so instead we must use a separate memory location for each device’s address. This can be done as follows: first we move

int n_gpus;

cudaGetDeviceCount(&n_gpus);

to the start of our C++ driver code, and then we initialize device array pointers as arrays with length equal to the number of GPUs,

double * d_x[n_gpus]; // not double *d_x;

For an example of what we are accomplishing by initializing an array of integer (pointers), for four GPUs on the V100 cluster this gives us pointers with addresses &d_x = [0x7fffdebe1a70, 0x7fffdebe1a78, 0x7fffdebe1a80, 0x7fffdebe1a88] which are unique and indeed these addresses are contiguous in memory. Then as we launch threads, each GPU’s thread gets a unique address for each array as we reference the pointer address corresponding to the thread number during device memory allocation

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(n_gpus)

{

int d=omp_get_thread_num();

cudaMalloc(&d_x[d], block_n*sizeof(double));

...

For example, if omp_get_thread_num() returns thread number 0 then we allocate that thread’s cuda array block to address &d_x[0] = 0x7fffdebe1a70. But why do we need different addresses if each device is different, such that there is no memory conflicts on the devices? This is becase we are accessing the address on the CPU in order to allocate on the device, and this access will lead to segfaults if enough threads attempt this at one time (depending on the hardware implementation).

Now that the kernel is complete(ish), we can profile it! Recall that the single-threaded multi-GPU kernel for 50k steps with 1000x1000 resolution completes in around 18.8s on a 4x V100 cluster. If we run our multithreaded version we find that completion occurs in around 19.1s, a little worse. This is because CPU threads are relatively slow to initialize, and in this case slower to initialize than the extra time necessary for one thread to allocate and copy memory to each GPU.

Multiple GPU memory deallocation

Thus far we have avoided the issue of memory deallocation for multiple GPUs. This is a more difficult issue than it otherwise might seem due to the under-the-hood implementation of cuda. First we will tackle the single-threaded multi-GPU kernel to illustrate the problem, and then use the knowledge gained to finish the multi-threaded multi-GPU kernel.

How would one deallocate memory on multiple GPUs and a single CPU? A naive approach to memory deallocation would be to simply free the host memory and then proceed to free each allocated memory block in each GPU, iterating through the devices one by one. As we are using pinned memory on the host, we have to free array x via cudaFreeHost(x); and doing so for all the arrays in the three body problem results in successful CPU memory deallocation. But if we implement this idea as follows

for (int i=0; i<n_gpus; i++){

std::cout << "Deallocating memory from GPU number " << i << "\n";

cudaSetDevice(i);

cudaFree(d_x[i]);

we run into an interesting problem: only the last GPU to have memory allocated (this happens sequentially remember when using one host thread) experiences successful deallocation. The other GPUs retain their allocated arrays until the host process is terminated.

This might not seem like a huge problem, but if this kernel is driven by a loop (say via a ctypes interface with python to make a zoom video) then the GPUs will eventually overflow. As each 64-bit 1000x1000 three body problem computation requires 452 MB in total per GPU, this occurs rather quickly. Moreover, depening on the hardware implementation a memory segmentation fault will be observed after a mere 2-4 iterations.

What these problems tell us is that the cuda interface forms a link between a pointer in CPU memory and its address for GPU memory allocation, and that critically only one link may be formed per CPU memory address. When one particular address in CPU memory (say &d_x = 0x7fffdebe1a70 for example) is assigned to one particular GPU via cudaSetDevice(d); cudaMalloc(&d_x, (N/n_gpus)*sizeof(float)); then that address may be re-assigned to another GPU’s memory allocation but the CPU will not be able to free the block it first assigned to the other GPU. This implies that cuda is changing the memory allocation procedure in machine code, as an array at one address in a GPU should be able to be de-allocated regardless of the sequence of CPU thread operations.

To remedy this, we can take a similar approach as to what was implemented for multithreading: instead of a single pointer we allocate d_x as an array of unique pointers, of length equal to the number of GPUs. Then we can proceed with de-allocation

for (int i=0; i<n_gpus; i++){

cudaSetDevice(i);

cudaFree(d_p1_x[i])

with this approach, memory is correctly de-allocated!

For the multithreaded kernel, we don’t have to re-iterate over GPUs as we can instead have each CPU thread free its allocated GPU arrays. As long as the memory of any arrays of interest is copied back to the host before freeing, we will get the result we want. cudaFree() is a synchronous operation such that we don’t really need to add cudaDeviceSynchronize() here, but it is added for clarity.

divergence<<<(block_n+127)/128, 128>>>(

cudaMemcpyAsync(times+start_idx, d_times[d], block_n*sizeof(int), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, streams[d]);

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

cudaFree(d_x[d]);

And with that we have working kernels for as many GPUs as we have in one node, using either one CPU thread for all GPUs or one thread per GPU. Practically speaking, a three body zoom video that takes around three days to complete on an RTX 3060 requires only two hours with a 4x V100 node.

We can check that indeed each GPU is run by one CPU thread by using htop. For the same four-GPU server as above, we find that four CPU cores are 100% utilized and each core’s process is running one GPU (which can be checked via nvidia-smi) which was what we wanted.

Parallelizing across multiple nodes is also possible with MPI (Message Passing Interface), but this will not be explored here.