Information between tokens

So far we have been observing the ability of the information in a transformer block’s output to represent some input. It may also be wondered whether only part of the output would suffice, as would be expected if the information from the input were to be sufficiently mixed among the transformer’s tokens before reaching the output. Elsewhere it was observed that vision transformers are generally much worse than attentionless MLP mixers at representing input regions not aligned to the output’s token.

We first repeat the procedure used in the page linked above: we give some target input to the model and then attempt to have the model generate that input using only the information in some output layer, specifically only the first x tokens in the sequence. For Llama 7b, it is clear that this language model also does not tend to mix information in the forward direction between tokens readily: given the prompt

\[a = \mathtt{The \; sky \; is \; blue.}\]For the first transformer block we have

\[a_g = \mathtt{The \; sky \; is \; blue \; fail}\]but if we restrict the output to $[:, :2, :]$ we have

\[a_g = \mathtt{The \; sky \; Sho \; advancedblock}\]Upon some reflection, it may be appreciated that this observation does not by itself mean that transformer-based language models do not share information between their tokens (more accurately the model’s activations at each token). This is because llama and other similar causal language models are trained to predict some passage’s next token, such that these models should never receive information from tokens to the right of the current token. This was not the case for vision transformers, where key, query, and value projections are performed amoung all tokens.

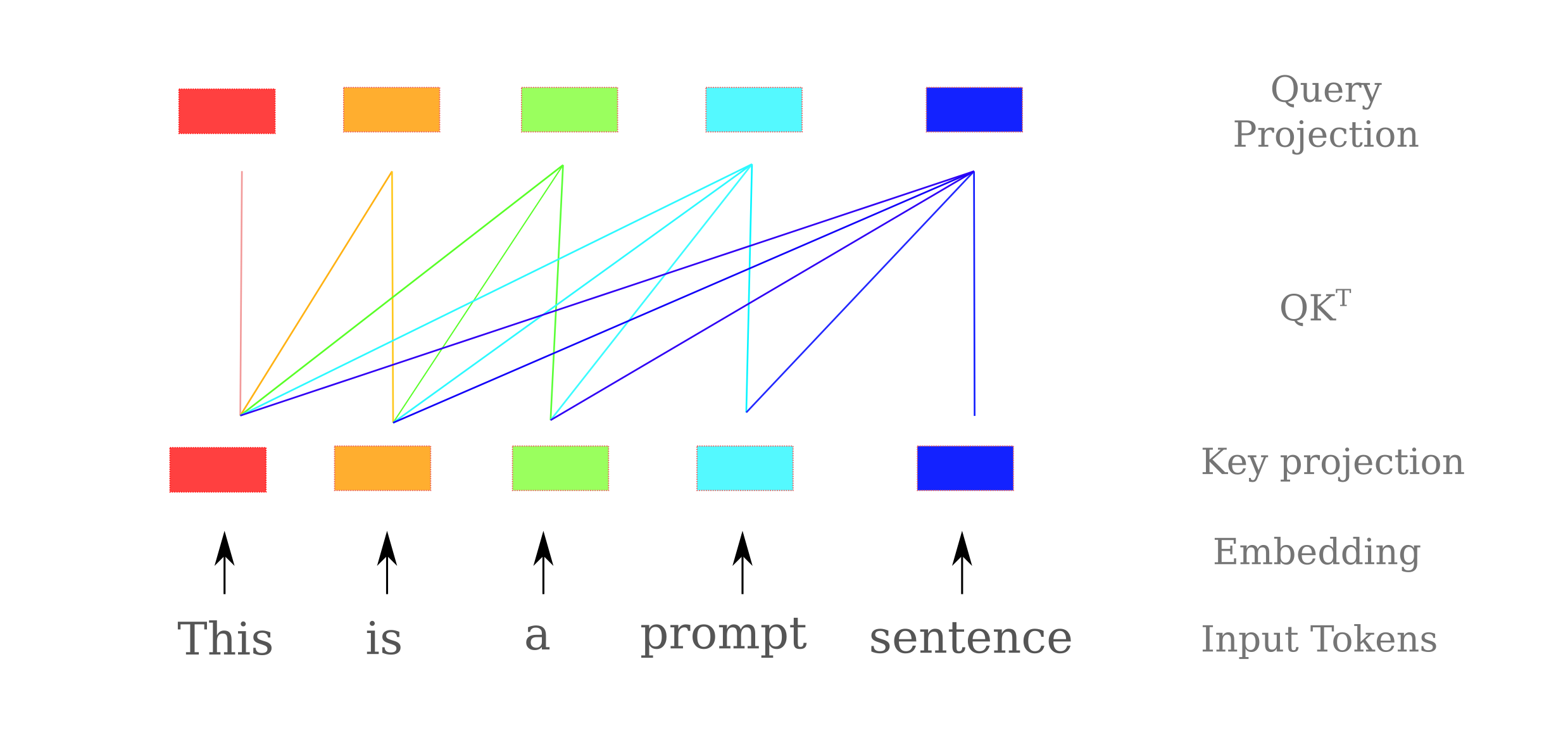

Specifically causal language models perform the query-key matrix multiplications as shown in the following figure: a token’s query projection is multiplied to all previous (ie left-oriented) token’s value projections (and possibly its own as well). This means that information in a clm transformer’s block can be influence by any token to the left of the current token, but not to the right.

For causal language models, therefore, we should instead check that a model’s activations for tokens after a given token are able to specify that input token if masked. Effectively we can ask whether enough information passes between tokens for the language model to determine the identity of the first two tokens, given the activations present in all following tokens. This may be done by restricting the output to $[:, 2:, :]$, which gives us

\[a_g = \mathtt{masterlex \; is \; blue2}\]indicating that for this input, the information present in the last three tokens (in the output of the first transformer module) is insufficient to determine the identity of the first two tokens. The same is observed for the input ‘This is a prompt sentence’, which for $[:, 2:, :]$ at the first output layer gives the representation

\[a_g = \mathtt{lex \; Sho₂ \; prompt \; sentence2}\]indicating that there is insufficient information transfer between later and earlier tokens to uniquely specify the masked tokens. Similarly, taking the output of the first transformer block of all layers except the first token for the input Four score and seven years ago gives lex score2 seven years ago.

It may be wondered whether a different metric might allow for more information to pass between tokens. In particular, consider the information that may pass between tokens via the multi-head attention transformation. Recall from the last section that given vectors $q, k, v$ the attention operation is equivalent to a scaled version of the following

\[A(q, k, v) = \mathrm {softmax} \left( q \cdot k \right) v\]although attention is usually calculated using matricies $Q, K, V$ such that the inner product $QK^T$ rather than the dot product is computed. Regardless, the information that passes between the query token (which for a causal language model is usually the last token) and the key token (typically one of the previous tokens).

The dot product may be thought of as a measure of vector alignment which is a function of both distance and angle, and in that respect it is perhaps unsurprising that optimizing a pure distance norm metric would be insufficient for information transfer. Instead one could optimize angle metric, for example the cosine distance (see https://blbadger.github.io/language-discreteness.html#indirect-input-representation-via-cosine-similarity for a more thorough explanation).

Given the somewhat lengthy input prompt

\[a = \mathtt{The \; sky \; is \; red \; or \; blue \; depending \; on \; the \; time \; of \; day.}\]we can test the accuracy of the input representation when the output of most but not all tokens is used to reconstruct the input. The direct input representation found cosine similarity for the trained 7 billion parameter Llama (taking the first transformer block only) for $[:, 3:, :]$ is

\[a_g = \mathtt{XI \; Macdet \; red \; or \; blue \; depending \; on \; the \; time \; of \; day.}\]indicating that the information in all following tokens for this prompt is insufficient to specify any of the first three tokens. This is also the case when both cosine distance and $L^1$ distance are minimized simultaneously (via optimization of a linear combination of these measures), meaning that even if we minimize both aspects of the dot product information still does not flow sufficiently between tokens to uniquely identify them.

A little experimentation convinces one that these findings are not peculiar to the choice of input sentence but are found regardless of what input if given to the 7 billion parameter version of Llama. This observation is also not limited to the Llama model family, as Mistral 7b experiences the same incaccuracy: for [:, 1:, :] from the first transformer block we have for the input Mario the man versus the idea

\[a_g = \mathtt{agenteli \; man \; versusPEGнал}\]and for The sky is blue the generated representaiton for the same output, the corresponding generated input $a_g$ is sky<s> blue<s>.

Being that we have seen larger models to be more and more capable at accurate input representation, it may next be wondered whether a larger model might be capable of more information transfer between tokens as well. Conceptually an arbitrarily large model would be capable of arbitrarily large information transfer between token model elements, but in particular it may be wondered if a somewhat larger version of Llama may be capable of accurate non-self token representation.

We test this by observing the ability of a model approximately twice the size of what has been used thus far: a 13 billion parameter version of Llama, again quantized to 8 bits per parameter. We try the representation gradient descent procedure first using $L^1$ distance, for the input This is a prompt sentence we have 作 is a prompt sentence if we use the information from all except the first token, ie $[:, 1:, :]$ from the first transformer block.

Likewise, for the 13 billion parameter version of llama when attempting input representation via cosine distance for the input

\[\mathtt{Mario \; the \; man \; versus \; mario \; the \; idea}\]we have Mario the man versus mario</s> idea if none of the model output is masked, and

if the first token’s output is masked after the first transformer layer. Increasing the number of transformer blocks results in a less-coherent input representation and does not improve masked token identification.

For the even larger 30 billion parameter version of Llama, given the same target input as above and taking all output except that of the first token ($[:, 1:, :]$) of the first transformer block, after optimizing the $L^1$ distance on this output (using indirect input representation) the input representation $a_g$ is

\[\mathtt{'rell \; The \; man \; versus \; mario \; The \; idea}\]And similarly for the input This is a prompt sentence we have the generated input representation $a_g$ of Dragon is prompt sentence <s> if the output of the first token is masked for the same model.

When we test this larger model’s input representation using a cosine distance metric, we again see that there is insufficient information to uniquely identify the first token: for the target input The sky is blue. the model yields an $a_g$ of quietly sky is blue<s> and for Blue is the sky. the representation is quietly is The sky<s>.

Upon testing a deeper layer (here the 8th transformer block) with the target input This is a prompt sentence. using an $L^1$ metric on $[:, 1:, :]$ we have

\[a_g = \mathtt{delta \; Gray \; wer \; prompt \; sentenceInd}\]And for the target input Mario the man versus Mario the idea minimizing cosine distance on all tokens ($[:, :, :]$) we have

\[a_g = \mathtt{Mario \; Inside \; man \; versus \; Mario \; Fund \; Mor}\]but when the output of the first token is masked,

\[a_g = \mathtt{ódbaum \; man \; versus \; Mario \; processes \; idea}\]In the last section it was observed that the cosine similarity metric could be used to find somewhat accurate representations of an input for an untrained Llama 7b, but only if the output of the attention layer rather than the output of the first transformer block (attention layer followed by two fully connected layers) was used to perform optimization upon. It may then be wondered if we might observe a similar phenomenon here: perhaps if we optimize the cosine similarity of an attention layer, the identity of a token whose output is masked may be found.

For untrained langauge models the representation for 7b and 30b llama is mostly the same as trained, but the untrained model exhibits one advantage: given the first transformer block’s self-attention transformation alone we can find accurate non-self token input representations using $\cos \phi$ as our metric: given the prompt Mario the idea versus Mario the man and the outputs $[:, 1:, :]$ we have a top-5 encoding of

Mario man the the Mario man idea

the the man Mario versus the man

la versus versus man the Mario Mario

isi Mario Mario idea idea versusperiment

Price система idea versus man↓ouvelle

and for Geralt of Rivia we have a representation Ger Rivalt Rivia given the output of all except the first token ($[:, 1:, :]$) and Ger Riv of Rivia for all except the first two tokens, $[:, 2:, :]$. As observed before, the tokens are often permuted such that the masked token is not necessarily in the correct place. It should be noted that accurate input representations for any input tokens are not obtained once more than one attention layer is used, or once attention is followed by the MLP layers that normally comprise a transformer block.

An aside: the keen observer will not that the information from the last token is able to apparently travel to earlier tokens, which should be impossible if each attention dot-product operation only takes place in the reverse direction. This is due to the a lack of a causal mask in the attention module, which would normally be added during the causal language modeling training process.

On the other hand, some experimentation is sufficient to convince one that this is not the case for trained models: for a 7 billion parameter trained Llama, the attention layer output does not yield accurate masked token identity.

It may be wondered why there is insufficient information passed between tokens for a trained model: which operation is required to pass information sufficiently between one layer and the next for a single token? This is easy to answer, and removal of each transformation in the self-attention module of a trained Llama (here is the source code) shows that the removal of the residual connection across the self-attention layer is alone capable of preventing even a single input token from being correctly identified (given complete outputs) regardless of what modules follow. As there are not residual connections between token elements in transformer models, it is little surprise in that sense that there is insufficient information to correctly identify the correct input token if that token’s output is masked.

Likewise, for an untrained Llama 7b we find the opposite phenomenon: removal of the residual connection across the first transformer block’s self-attention layer results in little change in input representation ability: given the input ‘Mario the idea versus Mario the man’ we have ‘Mario man the the versus man idea’ without residuals and ‘Mario man the the Mario man idea’ with residuals intact. Once again we find that input representation is quite inaccurate when more than one transformer layer (with or without residuals) is stacked.

Before concluding that insufficient information passes between tokens (via attention transformations) for accurate non-self token identification, however, consider that one might have made a similar conclusion for self-token identification when using models smaller than ~1 billion parameters, but larger models (7 billion parameters and larger) do turn out to be capable of accurate self token representation (due to their increase in layer width, which parallels a communication line’s bandwidth). We may wonder if the same phenomenon would not occur for non-self tokens.

A little experimentation convinces us that an increase in model size is indeed sufficient for non-self token representation: if we initialize one transformer module of the same dimensions as the 70 billion parameter Llama-2 as follows

llama_config_kwargs = {

'hidden_size': 8192,

'intermediate_size': 4*8192,

'num_hidden_layers': 1,

'num_heads': 64

}

# Initializing a LLaMA llama-70b style configuration

configuration = LlamaConfig(**llama_config_kwargs)

model = LlamaForCausalLM(configuration).to(0)

and using indirect input representation (minimizing an $L^2$ metric on the output) we find that the generated input for an output where the first three tokens are masked such that the output is [:, 3:, :] for the input Mario the man versus Mario the idea we have a top-2 token representation of

Mario the thecenwijні the

versus Mario idea man到 versusору

and if all tokens but the last are masked ([:, -1, :]) we find

versus census thegg canad Marioárt

where the non-self tokens for Mario, versus, the are correctly found, even if they are not in the correct token index (note that as for other randomly initialized, untrained models the exact input representation is somewhat dependent on the weight initializations).

For the trained 65 billion parameter Llama, however, the same prompt ‘Mario the man versus Mario the idea’ for the output of the first transformer block without the first token ([:, 1:, :]) representation of

which indicates that the self-token representation improves upon training, but the non-self token representation ability does not (the full [:, :, :] representation is MarioThe man versus Mario The idea). Similarly, for [:, -1, :] we have a_g = absor verb ForumFOimerwho idea, meaning only the last token is found. This is not peculiar to the chosen prompt: for example, not one of the top-5 representations for The sky is blue. finds the masked first token for [:, -1, :],

ignation sky is blue?

CC Skyson Blue when

okaysky COblueriften

broke publishebrace “

bo System AskFur

or for different models: the trained 70 billion parameter Llama-2 gives for Mario the idea versus the man a top-5 representation for [:, 1:, :] of the first transformer block of

Priceww idea versusww man

existed…aire vs…ww

港 the ideasww the Man

histor fils winningining cacheono

limitedэ mostly Pitts’ await

none of which correctly identifies the masked first token.

Even if we restrict the vocabulary such that the represented tokens may only be those that are found in the following sentence: A sky is blue or red depending on the time of day, and further depending on the size of the vocabulary present. for the input The sky is blue, we find an $a_g$ of ` size sky is blue`.

It may therefore be wondered just how large a model must be in order for non-self tokens to be accurately represented. For untrained models, the chance of accurate masked token representation depends on parameter initialization but increases with model size: perhaps 1/5ths of models with a hidden dimension of 4096 (Llama 7b size) but more than 4/5ths of models with a hidden dim of 8192 (llama 70b).

To conclude, we find that there is insufficient information passing from one token to another via self-attention for trained large language models to uniquely identify inputs in which the corresponding token’s hidden layer activations are masked. The lack of information transfer between tokens is observed regardless of whether a distance, angle, or combination of distance and angle metric is used to optimize the input’s representation similarity to a partially masked target. If this model is representative of others, the finding implies that transformer-based language models typically do not transfer sufficient information between tokens (via QKV matrix multiplications) for unique token identification.

This conclusion is similar to what was found for vision transformers: unlike MLP mixers (which accurately represented masked tokens), vision transformers were found to be unable to transmit sufficient information between tokens for accurate visual representation of tokens using the information in the hidden layers of other tokens.

Mixer Information Transfer

In the last section it was observed that large untrained language models are capable of accurate non-self token representation (although the tokens may not be in the correct sequence index), but that this ability vanishes during the training process. Similar conclusions were reached elsewhere for trained dot product attention-based transformers but curiously not for MLP mixer models that replace the self-attention operations with matrix multiplication operations. It may therefore be wondered whether an MLP mixer model might also be capable of accurate non-self token representation for language, as is the case for vision.

An implementation of a language mixer may be found on this page, but the main idea is that one replaces the self-attention transformations with a 1-dimensional convolution (such that all feature neurons from a certain input element are multiplied by the same weight, and all these multiplied values are added together) to share weights among a token’s feature neurons, but not between sequence elements. There are actually two sequential convolutions (separated by a nonlinear activation) connecting each pair of token’s feature neurons, and we use a triangular mask on the convolution weights in order to allow for causal language modeling.

Note that in this section, we use a 4096-size tokenizer fitted to the TinyStories 2M dataset such that the name Mario now takes two tokens.

When we test the untrained mixer on both self- and non-self token representation, we find that the model size requirements for accurate input representation appear to be similar to the transformers, or perhaps slightly more : for example, given the output of all tokens ([:, :, :]) of the input

Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

For untrained models, one mixer block exhibits a perfect input representation of Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man for $d_{model}=32$ and larger. For the mixer with expanded convolutions between tokens, non-self representation is less impressive: an untrained mixer with $d_{model}=512$ with an expansion factor of 1 yields

it, but ario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

And the situation is not helped with training: recall for one transformer block of an untrained $d_{model}=64$ mixer, we have a perfect input representation for Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man, but we find that non-self token representation is much worse. For [:, 1:, :] we have (ignoring trailing tokens) from the first mixer block

selessonario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

which is no better than the untrained model’s representation,

Cario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

Similarly, a trained $d_{model}=256$ does not correctly identify the first token, and gives a representation of

iario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

With a non-expanded (ie ‘flat’) convolution between sequence elements, non-self tokens may be accurately found: for untrained mixers we have for [:, 1:, :] at $d_{model}=512$ (given the first block),

Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

This accurate self- and non-self token representation persists after training for that model, if we take the information in a slightly deeper layer (say the output [:, 1:, :] of the second mixer or fourth mixer block). What is more impressive is the trained flat mixer’s representation given multiple masked tokens: for the output [:, 3:, :] of the second block we get a perfect input representation.

Reducing the hidden dimension leads to inaccurate non-self representation for the flat masked mixer, as for $d_{model}=256$ the representation is iario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man. It may be wondered if a linear combination of 1-dimensional convolutions (ie in parallel rather than in series) would yield even better non-self token representation, and after some testing it does indeed: before training, if we have two parallel 1D convolutions rather than one (added together to make our linear combination) then representation is extremely acurate: given [:, 10:, :] of the last mixer block (8) for a relatively small model with $d_{model}=64$, the input Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man is perfectly represented.

If we look deeper into an untrained flat mixer model, on the other hand, for $d_{model}=1024$, at block 8 we find

Marario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

and for $d_{model}=2048$ at block 8 we do find both accurate self and non-self token representation. This is also true if we scale the depth of the model without increasing the width, for example for $d_{model}=1024$ and $n=24$ layers we have also have a perfect self- and non-self representation for an untrained model (note that the n=8 layer version above was not as capable). What is more remarkable is that even if the first three tokens are masked, the representation is still perfect.

Model Invertibility

At the end of the last section, we have seen that an untrained masked mixer’s final layer representation is sufficiently powerful to identify nearly all or all of a short prompt’s input tokens.

Masked mixer input representation ability decreases somewhat upon training. For example, the flat $d_{model}=1024$ explored above retains perfect input representation of Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man for one mixer block, but after 8 blocks we have for [:, 1:, :]

Mgiftio, the Idea</s>versus Mario, the Man

which is slightly worse than the perfect representation present in this model before training commenced. Note, however, that the non-self token ‘M’ was accurately found.

This flat mixer representation is more accurate than that obtained from a similarly sized transformer (even when using the same 4096-size tokenizer and training dataset): a trained $d_{model}=256, \; n=8$ transformer (llama style) model yields for [:, 1:, :] the input Mario, the Idea, versus Mario, the Man

pictureario, the Idea, th let fterMarioiMan

where some self- and the non-self token are incorrectly identified, although for a trained transformer with $d_{model}=512$ we have

s. They whistch whistsat panstayou're snowpatophch whistsat Man

From these results it is apparent that masked mixers remain at least somewhat invertible after training, whereas transformers are less so.